It’s Google’s world, which means we’re always leaking data to them.

Some of us assiduously search for other options. But it’s not easy.

Two reasons: We don’t have a firm grasp of the size of the elephant we’re confronting, and secondly, we don’t really understand what we’re doing when we’re online. What data are we leaking, and how, and what does that mean? Is it something we should be worried about? If we wanted to limit our exposure to any one conglomerate, how would we go about it?

Inspired by the recent publication (PDF, as are many of the links in this piece) of the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority on ‘Online platforms and digital advertising’ , I thought I’d take a stab at prodding at least part of this animal.

Let’s take a look at browsers.

At least on the desktop (meaning laptops, PCs, anything that’s not a small-screen device) we spend a lot of time in the browser. (The opposite is true on mobile: eMarketer found in 2019 that 90% of time on mobile is spent in apps, rather than the browser. But as you’ll see, that doesn’t really help.)

So where does Google sit in all this?

You can have any colour you like, so long as it’s chrome

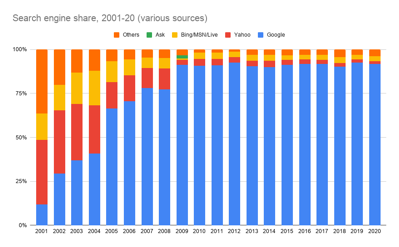

Google launched its Chrome browser in September 2008. At that point it seemed a somewhat silly thing to do — as the chart below shows, Microsoft’s Internet Explorer dominated the browser world (by virtue of Windows, which was on 90% or more of computers) and to a lesser extent Mozilla Firefox (the data below probably exaggerates its market share around that time).

Google made a splash when they launched the browser (Sundar Pichai headed the team) but played it carefully, saying that they would work with the Open Source community, were just continuing on their path, and promised the browser would just get out of people’s way: “The web gets better with more options and innovation,” Sundar was quoted as saying. “Google Chrome is another option, and we hope it contributes to making the web even better.”

Sure. I was excited too, and like everyone else went ahead and installed it, feeling that I was contributing to an exciting, and exclusive, new way of browsing.

So how do things look, 12 years on? It’s no longer exactly ‘another option’. It’s the option:

You can see how Microsoft (orange), asleep at the controls, allows Google (blue) to come from nothing and within a few years completely destroy it — and Firefox (green) for that matter. Where Microsoft had destroyed Netscape, so Google destroyed it.

So Google has what it wants. But what does it get with this browser dominance?

Data. Lots of it. Google has an insatiable appetite for your data, and has tweaked its privacy policy to ensure that it’s collecting as much of your data as it can across everything you do.

In 2012 Google introduced a policy that deliberately and explicitly connected all an individual’s data across all its platforms and services. Here’s how the Competition Law Forum (CLF) at the British Institute of International and Comparative Law put it in a submission to the CMA: “In 2012 Google announced the introduction of a new privacy policy that would encompass all the services Google offers, including popular services such as YouTube, Chrome, Google Play and Google Maps, replacing the previous individual’s policies that governed each service. Said privacy policy authorises Google to gather detailed personal data from any of those services and combine it for the purposes listed therein, including to create consumer profiles that are valuable for advertising purposes.”

Combining all this data is exactly what advertisers want, and the way that Google maximises the value it extracts from you. That’s why it has so many services — they are touchpoints, places where Google can, effectively, spy on you and know where you are, what you’re doing, and crucially what you want or intend to do. If you don’t think you use much of Google’s services, check out this site which lists all their products and services. You might be surprised.

Whatever browser you use, we got you covered

Here are some things that happen irrespective of what browser you’re using (if you’re on Android see below):

- If you use any Google tool that requires your signing in, then it will be able to track your activities, and match it to your profile.

- Even if you’re not signed in, Google will still collect information via the browser (or application, or device) you’re using.

- If you sign in to any Google service, then you will be automatically signed in to all other Google services — or services you’re using via Google’s single-sign on, whether or not you have them open on your device.

Chrome is where the heart is

And if you’re specifically using Chrome:

Signing in to any Google service

If you sign on to any Google service in Chrome, Google will automatically sign you in to the browser, thus linking, or at least potentially linking, everything you do in that browser to your profile.

Clearing your cache and going Incognito

Even if you clear your browser cache, Google can still track you via a persistent identifier (called an X-client-Data header) in Chrome. According to a lawsuit this identifier is within the browser Google can track you even in Incognito (private) mode. “In short, if you are using Google’s Chrome browser, Google’s code in that browser sends information back to Google’s servers identifying the specific, individual browser (associated with you) that is viewing any Webpage that has implemented Ad Manager, Google Analytics, the Google Button, Google Approved Pixels, etc,” the lawsuit claims.

A report on the lawsuit is here.

Passive data

While this piece (and the data) is mainly about Chrome on the desktop, it appears that Chrome on the mobile phone (in Android) is sending “data to Google even in the absence of any user interaction,” according to Douglas Schmidt of Vanderbilt University, quoted in the above lawsuit. “Our experiments show that a dormant, stationary Android phone (with Chrome active in the background) communicated location information to Google 340 times during a 24-hour period, or at an average of 14 data communications per hour.”

A separate report by Digital Content Next in 2018 found that two thirds of information “collected or inferred by Google through an Android phone and the Chrome browser was done through ‘passive’ methods, that is where an application is set up to gather information while it is running, possibly without the user’s knowledge.”

Sludge techniques

In the past — I couldn’t replicate this, so I’m not sure it still happens — Google would try to deter users from changing their default search engine in Chrome. This according to a submission by ‘privacy-priority’ search engine DuckDuckGo to the CMA. (DuckDuckGo uses Microsoft’s search engine Bing.)

Don’t take my word for it

The report just issued by the CMA concludes: “Google has developed unrivalled access to data through its operation of the largest browser (Chrome) and the Android mobile operating system. “

The report goes further. While it acknowledges that Google has said it is considering phasing out third-party cookies, which have become a target for those seeking to increase browsing privacy, this may end up making Google’s position even stronger. “(T)hrough its control over the leading web browser (Chrome) and mobile OS (Android), Google can also influence standards (such as support for third- party cookies) that affect rivals’ ability to collect and use targeting data (eg users’ browsing behaviour).”

Google hasn’t been great about explaining itself

Google has had a chance to say its piece to the group putting together the report. But you can’t help feeling they still don’t quite get it. Here’s a screenshot from a ‘non-confidential’ version of their submitted reply. If you have to black out a portion of a reply about the mode that in theory protects your users from snooping the most, you can’t blame them for still feeling a bit icky:

Successful in doing what? Persuading users they’re safe when they’re not? In collecting data when they think they’re not? Why would this bit be blacked out? It doesn’t seem like it’s hiding a commercial secret. Weird.

The Chromium wedge

It should be pointed out, as the CMA has, that Google has an extra lever: its control of Chromium, the engine on which Chrome is built. Microsoft, Opera and Vivaldi are all built on Chromium, open source software that Google controls, and which also powers the Chromium OS, the operating system which runs a dozen or more low-power laptops called Chromebooks made by Samsung, Asus, Acer, HP, Toshiba, Lenovo and Google itself.

You’ll see a list of them if you visit that link. But tf you visit the Chromium home page itself, you won’t see links to other browsers running Chromium. Other than Google’s own:

You can’t help wondering, given Google’s past in slowly building up dominant positions, firstly in search, and then in the browser, that they’re trying to do something similar with the computer operating system. Yes, Chromium is pretty piddling when it compares to Windows of MacOS, but that’s not the point. With Chromium the browser they now have leverage over Microsoft — who would have thought that? — the minor players like Vivaldi and Opera. As I will explain elsewhere they have control over other players in different ways. Just because they haven’t used that leverage doesn’t mean they can’t. Remember how they eviscerated RSS by controlling the RSS Reader market? I do.

(I will be exploring Chromium in a future post but it’s worth pointing out that Chromium underpins many apps and ads beyond the browser. According to 51Degrees.mobi Ltd, a mobile and data consultancy which submitted its own findings to the CMA: “Chromium is everywhere. Beyond classic web browsers including Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, or Samsung Browser, Chromium underpins many applications and advertising. For example, a web page or advert displayed withing the Facebook application is displayed using Chromium. An advert tapped within an Android application appears within a Chromium controlled experience.”

Bottom line

I’ve loved Google products for a long time, and I still use a lot of them. And as a journalist I found Google a much easier company to deal with than the other US tech giants. But I never got useful answers out of them when things got tricky, and as this topic highlights, they’ve never been properly candid about what data is being collected and how it’s being used. I don’t pretend this little stick-prod is going to pry anything useful out of them, or really help you make a decision about whether to change your online behaviour. Neither do I pretend their rivals are any better.

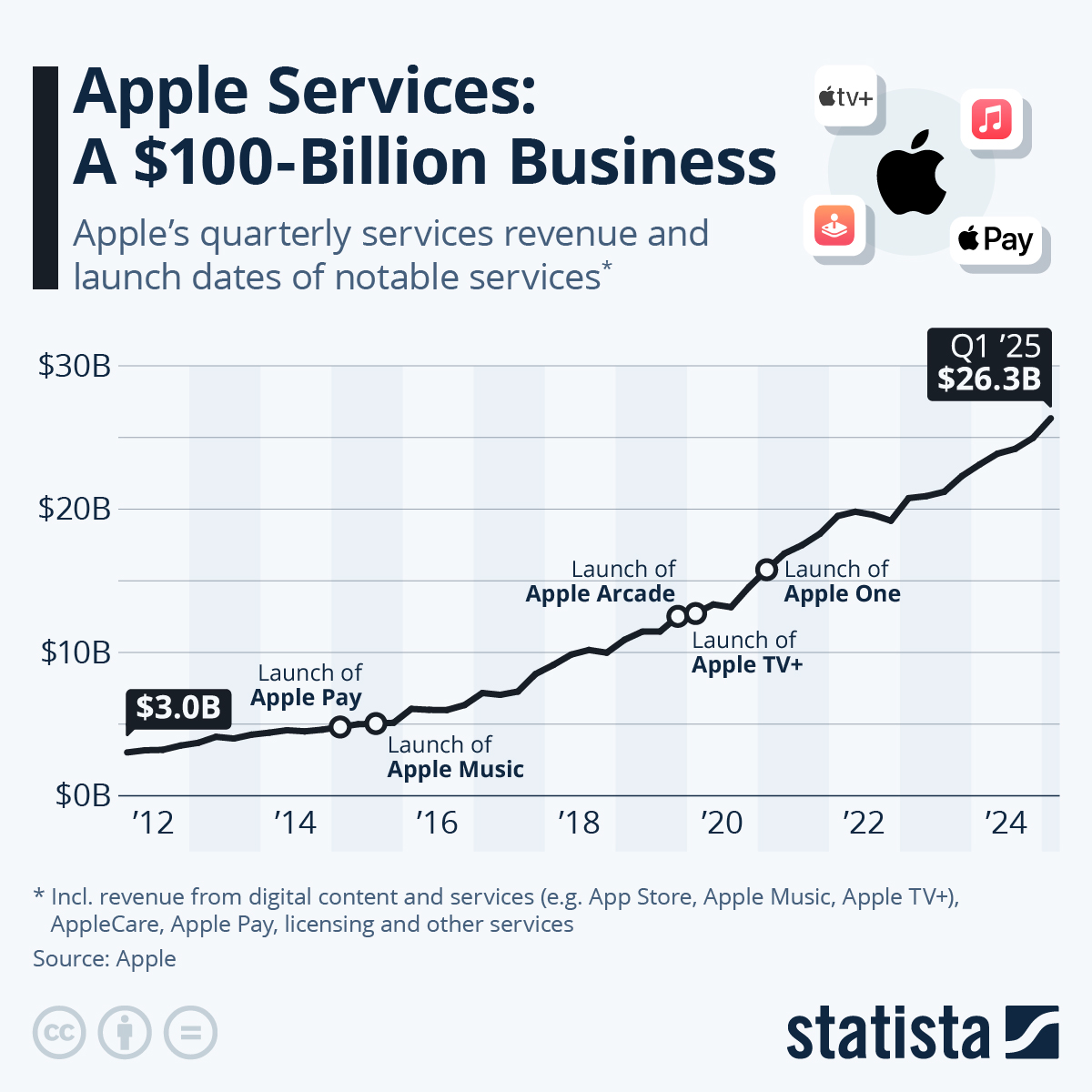

But I want to give a clap or two the CMA for at least trying to figure some of this stuff out and to map some of the ecosystem that generates all this money (including Facebook, which I’ll take a look at in future columns.) It’s a shame the UK is not part of the European Union anymore. A report like that with the EU behind it could have started some waves.

Transparency: In my role at Cleft Stick, I have done consulting work for Microsoft, a competitor to Google on some of these issues, on unrelated issues. I have no NDAs that I believe would affect my point of view.

- GOOGLE ADVERTISING TOOLS (FORMERLY DOUBLECLICK) OVERVIEW Last Updated October 1, 2019, paper prepared by Oracle

(“Oracle–ResponsetoSoS–Appendix1–DoubleclickOverview.pdf”) ↩

- Google Sundar Pichai has explained it in a letter to the United States House of Representatives Judiciary Committee: “When a user conducts a search on Google in Chrome Incognito and signed-out modes, we set a cookie to correlate searches conducted in the same Incognito window during the same browsing session… We will, however, use certain factors … such as the browser type, language, time of search, location (or an estimation of location), and prior browser session searches, to improve Search ranking relevance for the user’s query.” ↩

- From the DuckDuckGo submission, see above ↩

- Paragraph 7:61 ↩

- Appendix 7, Paragraph 114. Others have pointed out that in fact phasing out third party cookies would strengthen Google (and Facebook). ↩