(No AI was used in the writing or illustrating of this post. AI was used in research but its results have been checked manually. This is another in a series of pieces exploring the frontiers between human and AI work. Here’s another.)

AI is here to stay, and it’s moving fast. We are a little like defenders of Khe Sanh, the Alamo, Rorke’s Drift, take your pick. The defensible perimeter is shrinking as AI turns out to be getting better and better at doing what we thought was an unassailable human skill.

I would like to try to alter that thinking, if I can, to present as just another kind of challenge that we’ve seen countless times before, We need to think of AI as a sort of horizontal enabler, kicking down the walls between professions and disciplines. Historians have traditionally been sniffy about people not trained as historians (John Costello, among others, tarred with the brush of being ‘amateur’ and not in a good way). We journalists are notorious for going from 0-80, from knowing nothing about a subject to parading as an expert after a few hours’ research.

AI is definitely replacing creative jobs, but many of those jobs in themselves relied on an expertise that was ported in. Duolingo, for example, has apparently fired most of its creative and content contractors in favour of AI. (I agree that the product will suffer as a result, but we need to keep in mind that this job itself didn’t exist until 2021.)

We tend to assume that our skills, training, education and experience are moats, but they’re not, really. The moats are usually artificially constructed — see how long we’ve had to live with the internal contradictions of quantum orthodoxy because of academic inertia and bias. We create degrees and other bits of paper as currency that limits serious challenges to conventional wisdom to a selective few, and are then surprised when the challengers come from outside.

The lesson here, I believe is that we shouldn’t be too precious about what we do that we can’t acknowledge that machines might be able to do it as well as us. Brian Eno, inventor of ambient music and a great mind, was quite happy to create an app that generated the very genre of music he invented, and still produces. He recognised that creativity could, under the right circumstances, be generated automatically by tweaking some variables.

Yes, we should rightly worry about the way AI is being used to make large sections of the creative (I use the term loosely, to include bullshit jobs and PR content creation) workforce redundant. But we should worry less about the fact and more about our standards. We are, as I have argued previously, decided to accept inferior quality — just good enough not to have users running their finger nails down the blackboard in frustration — and not demand a higher standard. This has less to do with AI, I believe, than with the way AI is used. While AI content is usually atrocious, it depends what you give it to work with. This is a function, in other words, of what is being fed into the bio harvester, rather than (only) the shortcomings of the bio harvester itself.

What we should really worry about is this: how do we encourage creative types to embrace AI and to leverage it to improve the quality of what they do and to create remarkable new things? We should be thinking: how do we keep ahead of AI? The answer: we use AI to do what we can do better and something that (for now) the AI cannot do on its own.

This means having a different attitude to work, to learning, to doing business, to thinking. The closest parallel I can think of right now is how online freelance workers have been working for the last 15-20 years. I wrote a story about this back in 2012, when I visited a town in the Philippines to see how a librarian had transformed her neighbourhood by switching to offering her librarian skills online, and then, having won her clients’ trust, upskilled herself to do more complex work for them, and hiring neighbours to help her. She and others I spoke to were constantly reinventing themselves, something that I think a lot of online workers do as an obvious part of their business. For them there are no moats, only bridges to new skills and better-paid work.

My x.com feed is full of people selling the idea that AI can churn out money-making work while you sit back and relax. Fine. This might work for a while, a sort of arbitraging the transitions from human to AI. But this is not (in the long term) what AI should be used for. Yes, it can definitely help us be more efficient — help us scale the walls of knowledge and competence that we did not view as either necessary or desirable. I, for example, ask AI to help me figure out bits of Google Sheets that I can’t get my head around, or how to automate the sending of transcribed voice notes to my database. It’s not always right — actually it’s rarely right — but I know its quirks and can work around them.

But this is small potatoes. I need to rethink what I want to do, what I want to be paid for, and how high I want to fly. I’m almost certainly going to put some people out of work on the way (I don’t have as much work for my virtual assistant as I used to, I’m ashamed to admit), but I’m sure I’m not alone in noticing that the demand for well-ideated and executed commercially sponsored content has dried up in the past year. I’m guessing a lot of that stuff is now done in-house with a bit of AI. McKinsey, BCG etc now all use some form of AI to prepare reports based on their own prior content and research.

In short, join the march to new pastures. But what new pastures?

The first thing is to acknowledge whatever trajectory you had in mind for your professional life may no longer exist. This is not an easy thing to accept, but it’s better to accept it now than to wait and hope. Whatever AI does badly today, or not at all, it will get better and better is all most people need. There are no moats, only ditches to die in.

I don’t know, of course, exactly how this will play out. We’ll need to get back at co-existing at AI, learning about the langauge we use to communicate with them (what is rather pompously called prompt engineering).

But that’s just the interface. The skills we develop through that interface could be anything. Think of the skills acquisition explosion that Youtube supports, such as channels that focus on manual crafts (Crafts people for example, has 14.2 million subscribers).

![Tim Radford, hedgelayer ([] https://www.wonderwoodwillow.com/hedgelaying-planting)](https://www.loosewireblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DraggedImage.jpg)

But we need to skate to where the puck will be, not where it is.

Indeed, the irony of AI may be that it helps our world pivot from digital to real, as politics and climate crisis push us to abandon our addiction to rampant consumerism and regain a respect for tools and products that last, and that we can fix ourselves.

More important though will be the new work that we can build on the back of AI. If I knew what those jobs are I probably wouldn’t be sitting here telling you lot, but be building them myself. But for the sake of argument let’s ponder how we might figure it out: we first need to identify a need that exists, or will exist (remember the puck) and that the need itself cannot be be done by AI, at least for the foreseeable future.

The most obvious one is the mess AI leaves us. I have never come across something done by AI that can’t be improved upon, or corrected. And we know that AI does not explain itself well, so even if AI can find the tumour a specialist couldn’t, we really need to know how it found it, even if it means trying to understand something that it is unable to explain itself.

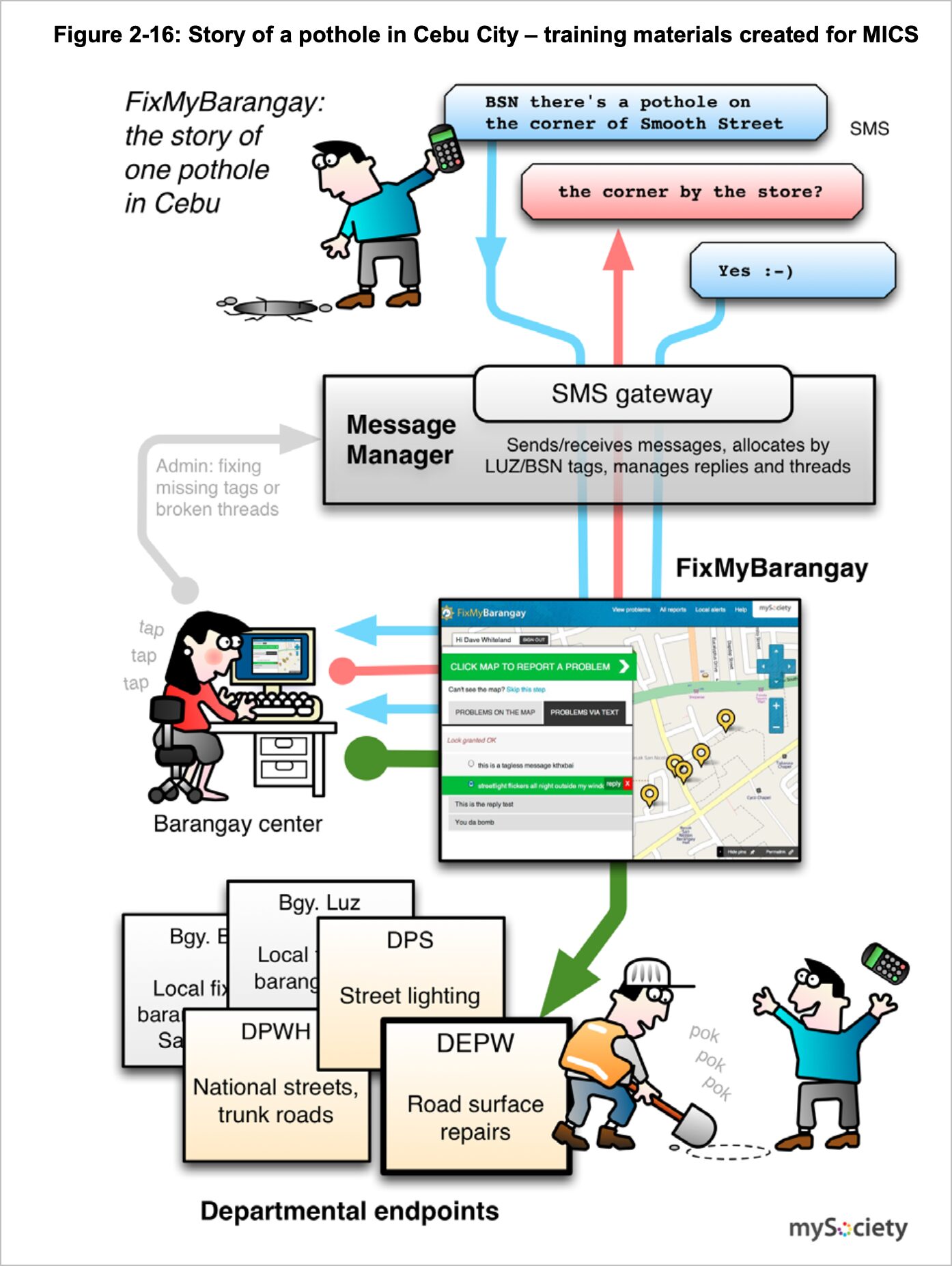

But there are bigger issues, bigger problems, bigger needs that we need to face. It is not as if there aren’t things that we need to do, we just never seem to have the money or the political will to do them. We are suffering an epidemic of mental health issues, and while I understand how AI might be helpful in easing some of that pain (particularly the pain of loneliness), but far better would be a process that expanded the cohorts of people with enough counselling skills to be able to connect to sufferers and help them, professionally or as part of their daily work. Instead of potholes being something reported and fixed by some remote arm of government, the process of collating data could be crowdsourced (I remember a World Bank pilot project in the Philippines in the early 2010s) and the work assigned to a nearby volunteer suitably skilled via AI in filling in potholes.

AI could and does help us acquire new skills that are not ‘careers’ in themselves, but can contribute to a blend of physical, mental and creative work that sustains our future selves.

Another way of looking for opportunities is this: What work would have been too expensive or too time consuming to be considered a business, and can AI help? Garfield AI, a UK commpany, offers an automated way for anyone to recover debts of up to £10,000 through the small claims court. This is potentially a £20 billion market — the amount of unpaid debts that go uncollected annually — and it’s probably one that is not manageable by most legal companies, and too cumbersome for small creditors. Here’s a piece by the FT on the company: AI law firm offering £2 legal letters wins ‘landmark’ approval.

This doesn’t mean that we can’t also be doing ‘mental’ creative work — using AI, say, to work out who is responsible for the mess that is the British water industry by creating an army of AI-enabled monitors and investigators, identifying polluters and making them accountable. This could be initiated by one individual with the smarts to figure out the legal challenges and to find ways to incentivise as many people as possible to gain the skills necessary to contribute effectively.

In other words: we need to stop thinking in terms of what jobs AI is taking and thinking what jobs that don’t exist that we can now do with AI.

Finally, a word on creativity. Creativity is, in the words of Eurythmic Dave Stewart, “making a connection between two things that normally don’t go together, the joining of seemingly unconnected dots.” That meant for him and Annie Lennox trying to find a connecting point between their talents — synths for him, voice for her — which as we know eventually paid off. Steve Jobs talking about creativity being “just connecting things.” It’s not as if AI can’t do this, but it can’t, according to researchers, compete with humans’ best ideas, their best connecting together disparate things.

I understood this a little better talking to an old friend who is a famous writer, but has been suffering from Long COVID since the pandemic. It prevents him, he says, from keeping in his head the necessary elements for a novel, but he can just about manage short stories. He still writes, and writes a lot, but that extra genius/muscle of creativity that has propelled him into the ranks of Britain’s best writers is currently not working properly. To me that explains a lot about what is really going on in human creativity, at least at the highest level. It’s frustrating for him, of course, but to me it’s an insight that should inspire us to make the most of our extraordinary minds, and to acknowledge that at their best our minds are no match for any kind of AI.