Interaction impoverishment: My pompous term for the things that we can’t do, and don’t seem able to imagine our way out of, when it comes to making our devices do what we want them to do. The key to all this — and where we might end up going — are down to those millimeter-dimension things we never see: sensors.

I was speed-watching George Clooney’s Netflix movie The Midnight Sky the other day, which is set 28 years in the future, and they’re all (well not all, because most of the planet is dead) interacting with their computers in the same way — touch screen and voice (George at least can turn off an alarm by voice, while those in the spaceship have to get someone to manually stop the alarm, the sound of which would be recognisable to someone living 100 years ago). I feel that we’ve learned enough from Alexa and co to know that voice is a poor form of interaction with our devices. Our dinner-time conversation at home is usually punctuated by someone yelling “Alexa… Stop!” in response to some alarm or other, and then, back in a dinner party voice, murmuring to our guest, “sorry, you were saying?”

And don’t get me started on trying to get Alexa to remember things, or disremember things. Most trails usually end up with her asking, politely, for us to use the app, to which we usually reply, less politely, that if we have to do that, what exactly is the point of, well, her? And I have NEVER, ever, seen anyone interact in public with their phone by voice, except when they’re talking to an actual human. I think we can safely agree that particular line of device interaction is gone. Siri is, to me, nothing. Convince me otherwise.

Another thing: using a mobile device in the rain, or with fingers that are even slightly moist, is an exercise in frustration. Fingerprint scanner doesn’t work, fingers on screen don’t work,. Whether I’m washing up or trying to take videos of rainfall, I yearn for the days of a keyboard (or a smarter voice interface, or anything.)

So why George et al haven’t come up with a better way to interact with their computers, I would guess is because we’ve done a poor job of it thus far. Shouldn’t we by that point have honed our brain-computer interface? (A study by RAND last year said BCIs, as they’re called, are close.)

Indeed, there are some gleams of light, though I’m hesitant to call them more than that. Google has something called Motion Sense, which is a sort of radar — emitting electromagnetic waves and learning from their reflections — that improves, in theory, the relationship between you and your phone. Firstly, it can detect whether you’re nearby, and if you’re not, it will turn off the display (or keep it on if you are.) If it senses you’re reaching for it, it will turn off alarms and activate the face unlock sensors. It will also recognise a couple of gestures: a wave to dismiss calls or alarms, a swipe to move music forwards or backwards.

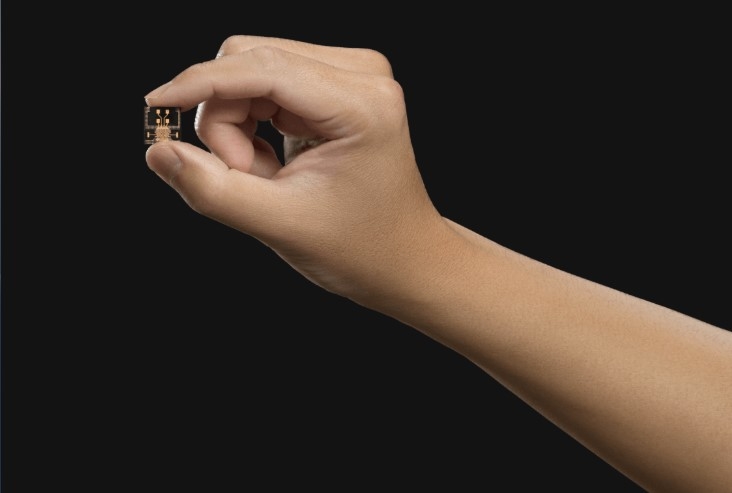

The jewel here is ‘presence detection’: Can a device be smarter about understanding what or who is around it, and behave accordingly? We’re used to this with motion sensors — lights coming on when we walk in a room, or alarms sounding when an intruder enters the house. But this is detection on a much smaller scale, requiring millimeter-wave frequencies by utilising the unlicensed V-band (57-64 Ghz) which makes measurements more precise and less likely to be interfered with by other systems. In short, Project Soli was enabled by a 9×12.5 mm chip produced in collaboration with Infineon, with a sensing range of 10 m and a range resolution of 2 cm (which can be reduced to sub-millimeter precision, allowing recognition of overlapping fingers. A paper published in 2019 concludes that accuracy of a ‘few micrometers’ (1,000 micrometers make up a millimeter) can be achieved with such sensors. This in theory would take accuracy of gesture down to a subtle eyebrow raise, or something even more inscrutable.

How this technology is used might not go in a straight line. Google introduced Motion Sense in its Pixel 4 smartphone, but removed it in the Pixel 5, mainly because of cost. There is solid speculation that the upcoming Nest Hub device has it. Kim Lee’s piece cited above from 2017 suggests it could be possible to control via finger-sized commands — pinching or snapping — and do away with visible controls altogether.

Of course other manufacturers are thinking along similar, or not so similar, lines. A concept phone (i.e. one that doesn’t actually exist) announced by OnePlus last December — the OnePlus 8T — included hand gesture interaction which included changing the colour of the device itself. (If you’re interested, this uses a ‘colour-changing film containing metal oxide in glass, where the state of the metal ions varies according to voltage.) What’s potentially interesting here is that OnePlus envisages the colour changing indicating incoming calls (etc — perhaps different shades, or flash rate, could indicate different things.) OnePlus also talk about using a mmWave chip to register a user’s breathing, which could then be synced with the colour changing. They call it a biofeedback device, though I’m still searching for the purpose behind this.

All this is welcome, but I do feel we could have gone further, faster. LG were touting gesture recognition in their devices at least 6 years ago (the LG G4, for example, recognised gestures in 2015 allowing you to take remote selfies etc), and we get occasional glimpses of what is possible with apps like ‘Look to Speak’, a Google app for Android that allows handicapped users who suffer from speech and motor disabilities to use eye movements to select the words and sentences they want from the screen, which are then spoken aloud by a digital voice. This requires some training however, and exaggerated movements.

Then there’s gesture control using ultrasound and light, something I wrote about for Reuters back in 2015. The idea is not to do away with our preferred way of interacting, by touch, but to bring the touch to the person using air, sound and light. A driver would not have to take his eye off the road to fumble for the controls, for example, but a virtual version of the controls would come to him, giving him haptic feedback through vibrations in the air.

To me this is a key part of any interface. Alexa will acknowledge an instruction, and our computing device will (usually) acknowledge in some way when we’ve entered a command or clicked on a button. But the touch is sometimes a better way to receive a response — it’s more private, for one thing. (My favourite example of this was a belt designed by a Japanese researcher which vibrated. Where the pulse was felt on the body determined the nature of the message. (Le Bureau des Légendes, an excellent French series on the DGSE, takes this a stage further where a CIA officer intimates that he gets alerts that his phone is being tampered with via a pacemaker.)

Sensors, ultimately, are the magic ingredient in this, but it’s also down to the execution. And if we’ve learned nothing else from the past 10 years, we’ve reluctantly acknowledged it’s usually Apple that brings these technologies home to us, at their pace. Apple thus far has gone with the LiDAR option — replacing the radio waves of radar with light — which, at least in the pro version of its recent iPhone and iPad releases, allows users to map a room or object in 3D, and then use it for design, decoration, etc.1 But it’s not like Apple to throw a technology into a device without a clear roadmap of either enhancing existing functions or adding new ones, so the most likely explanation is that LiDAR helps improve the quality of video and photos by tracking depth of field etc. But it almost certainly won’t stop there; Apple is betting hard on augmented reality, for which LiDAR is well suited, and a study of Apple’s patents by MaxVal suggests possible new directions: using LiDAR to generate a more realistic 3D image on the screen, for example, by better judging the position of the user’s head, say, or better Face ID.

I’m open to all that, but I really feel some of the basics need tweaking first. Ultimately it’s about our devices understanding us better, an area in which I feel they have some ways to go.

- Some Android phones like Samsung’s use LiDAR, but this version uses a single pulse of light to scan a space, vs the multiple pulses of Apple’s LiDAR ↩