It’s easy for most people — journalists included — to look the other way as Julian Assange’s case grinds to its (likely) grim end. He doesn’t fit neat holes — is he a journalist? An activist? A political operator? A source? An intermediary? A publisher? A whistleblower?

This means that those who are supporting his case are a rather motley bunch, from the left (the late John Pilger, Jeremy Corbyn, Noam Chomsky) to the far right (Tucker Carlson, Sarah Palin, for example). And then there are people in the middle, who feel that both principles and laws are being trampled upon. (Opposition to Assange is also a varied crowd, including Hillary Clinton and Mitch McConnell.)

This should create a broad coalition, but opinion towards Assange is not fixed. When a UN panel ruled in 2016 that Assange had been held arbitrarily by the UK and Sweden, two thirds of Britons surveyed disapproved the ruling. While there was crowd outside the court for deliberation on his extradition, a petition to grant amnesty to Assange posted on Avaaz.org in 2019, has been unable to reach 300 signatures and his name is nowhere to be found on the website’s homepage. Indeed, the sheer length of Assange’s case — running for 14 years now, since Swedish prosecutors issued an arrest warrant for him in 2010 — makes consistent support and publicity for his case difficult.

Chilling episode

So why should we care?

Whatever happens to him, Assange will leave a significant legacy. He changed journalism in a way most of us in the profession are reluctant to acknowledge. It’s now commonplace for journalists and newsrooms to actively solicit secret documents, and advertise the lengths they will go to to protect the source. While investigative journalism didn’t start with Assange, he helped usher in a minor revolution in the occupation — not least by the trove of stories written based on Wikileaks material. Journalists, in the words of Christian Christensen, a Sweden-based professor of media studies, should recognise that “Assange was a key part in the journalistic process, and by criminalising his participation you thereby criminalise that process.”

In my view, there’s one thing that Assange did that makes his freedom a moral requirement. It is his release on April 5 2010 of a video that Wikileaks called “Collateral Murder.” The 39-minute video, obtained by Chelsea Manning, is the view of a Baghdad street from an Apache helicopter gun-sight on July 12 2007, and in Wikileaks’ words “clearly shows the unprovoked slaying of a wounded Reuters employee and his rescuers.” The video, and the accompanying radio-chatter, combine to engrave a chilling episode in the history of warfare, comparable to the images of a Vietnamese girl, Kim Phúc, caught in a US napalm attack, the torture of Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh and other Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib, or the image of the body of Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi, 3, washed up on a Turkish beach in 2015.

There’s a long backstory to (and fallout from) this case which I won’t repeat here. But certain points are worth stressing (I should declare an interest; I am a former Reuters employee, and I am friends with Dean Yates, the Reuters bureau chief in Baghdad at the time of the incident. Much of the following is taken from his 2023 book Line in the Sand; a statement by Dean was submitted to the court currently considering Assange’s extradition).

Hostile intent

Reuters had been shown only a small fraction of the recording in the wake of the killing, which in isolation seemed to support the US army argument that the helicopter crew had good reason to believe the group, which included two Reuters journalists Saeed Chmagh and Namir Noor-Eldeen, also had among them a man apparently carrying a rocket-propelled grenade, or RPG. They could be ‘engaged,’ Dean is told, because the presence of supposedly armed men was an expression of ‘hostile intent.’

Reuters was not allowed to keep a copy of the video or any of the material shown to Dean, and the company had been trying to obtain the video through legal channels unsuccessfully up to the time of its release by Wikileaks. The U.S. had blocked such requests at every turn, telling anyone who asked that it couldn’t be found.

The release of the full video by Wikileaks three years later showed several things: firstly, that the subsequent attack on the family trying to rescue the injured likely broke not only the Geneva Convention on attacking wounded, but also the military’s own rules of engagement. In his book Dean describes the video this way:

“It was pure truth-telling. No military officials could deflect, sanitise, provide ‘context’. There is also no tape like it from any war in history in public domain.”

This public domain aspect is key, and perhaps goes to the heart of Assange’s take-no-prisoners approach. Dean points out the only comparable video of an alleged war-crime happening is the execution of a communist Vietnamese prisoner, Nguyễn Văn Lém, by South Vietnam’s police chief Nguyễn Ngọc Loan on 1 February 1968. A photo of the moment when the is accessible enough, but the video remains the property of NBC and can only be obtained with special permission. “Everyone remembers the Pulitzer Prize-winning photo by Eddie Adams,” writes Dean. “But not the footage because it’s not a mouse-click away.”

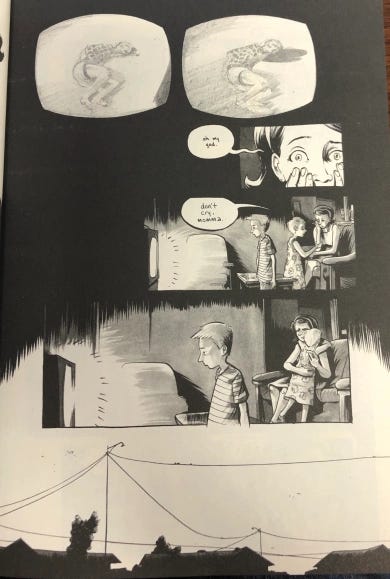

Watching the execution of Nguyễn Văn Lém: from Mark Long, Jim Demonakos, and Nate Powell’s The Silence of Our Friends, via Interminable Rambling

Moving snapshot

When the video was first aired on NBC in 1968 it “led people to see major problems with the war,” in the words of Safia Swimelar, Political Science and Policy Professor at Elon University. “Many have said that photo and video also just illustrated the moral ambiguity of the war, since it showed that both sides were engaged in violence and possible war crimes.”

By making the Iraq video available with a mouse click, it could be argued Assange has ‘cheapened’ the content, desensitising us to its horror. But probably the opposite is true. We know that it’s there, a defiant finger to the authorities that tried to hide it from the families of the deceased and others seeking the truth about what happened, and, more generally, what the war in Iraq really looked like. It’s understandable that NBC wants to maximise its asset, but it could also be argued that it should by now — 56 years later — at least be in the public domain, a moving snapshot of the Vietnam War as much as Collateral Murder has come to define the Iraq conflict.

Neutral technology

It’s also clear that the U.S. knows it is on shaky ground. While it formed a key part of Chelsea Manning’s indictment, the video is not mentioned anywhere in Assange’s indictments. It’s likely that the U.S. really doesn’t want to go down that route: Much of the rest of Wikileaks’ (and Manning’s) material is that it shows professionals — soldiers, diplomats, analysts, spies — going about their work.

The secrets revealed, whether or not they’re in the public interest, are those that might embarrass a government or highlight its hypocrisy, or possibly endanger a U.S. official going about their proper business. Collateral Murder, on the other hand, exposes something different: not just the abuse of existing rules of engagement, but the absurdity of the “notion of neutral technology at the service of human development,” in the words of Christian Christensen, in a 2014 paper on the ‘afterlife’ of the video. Armies make particular effort to characterise their weaponry as smart in their behaviour, surgical in their impact, and while most of us know this is not really the case, it takes behind-the-scenes videos like this to remind us. Technology in war rarely reduces the harmfulness of a weapon, least of all for bystanders.

Secrets impose a cost, usually on the victim or their loved ones. To properly understand their wound they need to understand what happened, and why. For Dean the video’s release began a journey, illustrating on a micro-scale how the truth, however unpalatable, can set you free. Dean has struggled with PTSD and its brother moral injury, in part because he had not come to terms with the incident and his own feelings about the two men he lost on his watch. The release of the video — the full, unvarnished truth of the incident as it unfolds — highlights how damaging the keeping of secrets can be. In his struggle to come to terms with his PTSD Dean sought the forgiveness of the families of Saaed and Namir, and also tried to reach out to the occupants of the Apache as well, hoping they might share their stories too, and “help the healing” of everyone involved, including themselves.

It’s understandable the U.S. doesn’t want to start discussing all this in public again. But it also helps illustrate a truism that we too readily forget: that governments keep secrets for the wrong reasons — usually to conceal from their own citizens that rules have been broken. But at the same time it goes out of its way to punish as severely as it can any individual like Manning or Assange — pour encourager les autres. That, so far, hasn’t worked: Think of all the whistleblowers who have followed in Assange’s wake — Snowden, Antoine Deltour (LuxLeaks), Maria Efimova (Malta), Reality Winner (NSA), Frances Haugen (Facebook), Hervé Falciani (HSBC), Rudolf Elmer (Julius Baer), the still anonymous Panama Papers leaker, Xavier Justo (1MDB), Howard Wilkinson (Danske Bank), nearly all of whom have through their bravery helped launch investigations and/or changes in policy, despite great peril to themselves and the journalists who report their stories. (Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was assassinated in 2017 for her work based on Efimova’s whistleblowing.)

Do we deserve the sacrifice?

By releasing the video Manning and Assange wrote themselves into the history books, showing the graphic truth of what advanced U.S. military power looks like in practice. Perhaps, 14 years on, we are still too close to it to recognise the impact of that truth — or perhaps we have too readily forgotten it. Both understood the gravity of the material in their hands — after retrieving the video Chelsea Manning immediately searched for the rules of engagement each occupant of the helicopter would have been carrying — but perhaps neither may have thought too deeply about the personal sacrifice they would ultimately be making. We should not blame them for that.

Still from Dunkirk (1958) , directed by Leslie Norman

In 1958 Michael Balcon of Ealing Studios produced a fictional film based around the evacuation of Dunkirk, not because he wanted to eulogise the recent past, but because he wanted to disturb audiences, which he felt by the late 1950s had grown complacent, individualistic, unworthy of the sacrifices made for their benefit. He wanted them to ask themselves: “Was Dunkirk worthwhile? Have we deserved the sacrifice? Do we remember what war is?” Assange’s fate is in our hands, and Collateral Murder is the evidence of sacrifices made — both by the people killed or wounded that day, and by a handful of individuals to bring that crime to light — that we should not ignore.