If your revenue model relies on misleading, impoverishing and gaslighting your customers, then you probably should rethink your model.

That would seem to be a reasonable statement to make, and one most businesses might agree with. But the reality is that companies are falling over themselves to charge people for things they didn’t ask for and to keep doing it.

In the UK alone, consumers in 2023 spent £688 million (US$912 million) on subscriptions they didn’t use, didn’t want, and didn’t know they had. That’s nearly double that for the previous year. These include those who didn’t realise a subscription had auto-renewed, signed up for a trial but forgot to cancel before the paid bit kicked in, or who thought they were making a one off-purchase. (I’m only using UK figures because they were the most credible ones I could find. It’s highly likely it’s the same elsewhere.)

Welcome to the subscription economy, which should more rightly be called the subscription trap economy. For the past decade it has been the business model du jour. And, possibly, it may be on the way out.

California has led other US states into implementing stricter auto-renewal laws, and the FTC is cracking down on “illegal dark patterns” that trick customers into subscriptions, and in the UK rules that limit predatory practices will likely come into force by 2026. The FTC has taken Adobe to court, alleging it had “trapped customers into year-long subscriptions through hidden early termination fees and numerous cancellation hurdles.”

Enshitification and the doctrine of Subscriptionism

I’m pleased they’re doing all this (and the EU, India and Japan also have legislated in this direction). But I’m not holding my breath. Subscriptions have been such a boon for companies they’re not likely to ditch them, or the dark arts around them that help make all this so profitable.

While I’m tempted to throw all this into the “enshitification” dumpster, it’s not quite the same. Enshitification means gradually eroding the quality of a free or near-free product in order to prod users to pay, or to make the service more profitable in other ways (for advertisers, for example). Subscriptionism, for want of a better term, is what happens after the enshitification has been successful. The customer throws up their hands, signs up for whatever gives them less enshitification, and then the company ensures, Hotel California-like,

- customers never leave because it’s too painful to figure out how to unsubscribe;

- they don’t quite realise how much they’re paying (or they never realise they are paying);

- that the paid service itself gradually enshitifies, pushing the user up to the next tier, which is merely a more expensive version of the original tier they were paying for. (Think Meta, Netflix, Max (ex HBO Max), Amazon Prime, X etc);

- rinse and repeat.

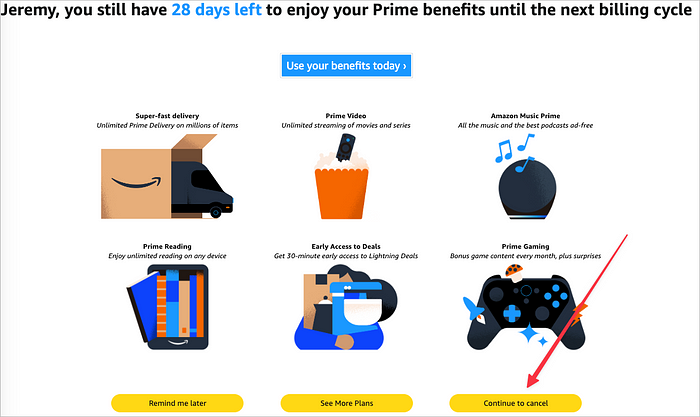

So no, I don’t think that companies will really make it easy for you to unsubscribe. It’s simple economics. Acquiring a new customer is hard, which is why it’s so easy to sign up. Churn, therefore, is the enemy. Companies will spend a lot of money on trying to keep you aboard. The FTC found that more than three quarters of subscription services used at least one ‘dark pattern’ (think misleading wording or buttons, etc), while EmailTooltester found that Amazon Prime was the worst offender, averaging 7.3 dark patterns per cancellation.

I can confirm this last one, and it provides a good illustration of the dark arts. When I get through to the right page, and click on Cancel Prime, I was greeted by a confusing page. It took me a while to figure out whether or not I actually had cancelled. It’s like a game of Where’s Waldo/Wally? I finally found out by looking at the bottom right corner:

So no, I haven’t. I don’t think so. Someone somewhere was paid big bucks to discombobulate me enough to think I had already canceled.

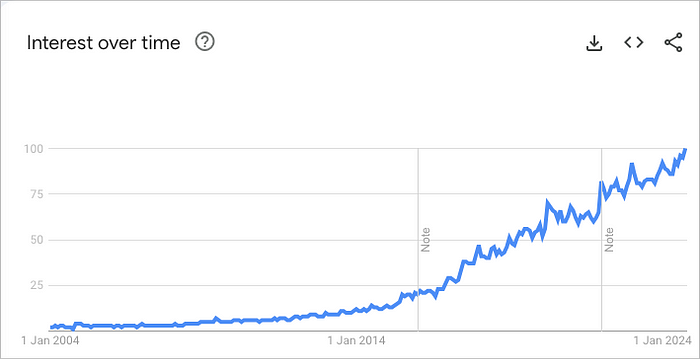

There is a correlation between such dark patterns and the problems Amazon is facing. Subscription, according to RetailX, an analyser of retail data, accounted for a 7.7% of Amazon’s total revenue in 2023, more than twice the 3.15% share reported in 2014:

However, the subscription share of Amazon’s revenue has plateaued in recent years. While it doubled between 2014 and 2018, when it made up 6.36%, it has risen by just under 0.5 percentage points in the following five years.

So while Amazon’s subscription revenue is increasing it’s nothing compared to Amazon Web Services, online stores and retail third-party seller services. If subscriptions were so damned wonderful, why would a company work so hard to not let you leave the shop?

The Dark Art of Notificationism

This is not a one-off. Researching this topic I came across Rocket Money which is supposed to help me figure out all my subscriptions and cancel those I don’t want. Or something like that: It only seems to work in the U.S. so I gave up. But by then I had an account and getting out wasn’t going to be so easy. I tried to unsubscribe from emails but was greeted by a page where radio buttons had been pre-selected for 20 different kinds of notification, and which required me to click on every single one to remove myself. When I tried to delete my account I found the option hidden at the bottom of a Profile menu, which required me to click on a unlabelled gear icon, and then to scroll down beyond the visible pane to find the delete account option. Even then it still wasn’t clear that I had actually removed my account: trying to log in to check instead requires me to set up Two Factor Authentication, via an app or SMS, before I could check. So I left it there and I will probably be getting Rocket Money notifications for the rest of my days.

The foxes are indeed in charge of the hen house. Rocket Money seems keener on adding me to their subscription world rather than help me unsubscribe from the others. Indeed, it’s interesting to watch the businesses who tout themselves as kings of this domain. Recurly, for example, presents itself as the “leading subscription management platform” and says it wants to help its customers “create a frictionless and personalised customer experience.” Amusingly, it lists as its clients six companies, five of which have themselves been criticised for cancellation issues.

The company is upbeat in its 2024 Subscription Trends, Predictions, and Statistics:

Over the past year, Recurly has seen a 15.7% increase in active subscribers, and when comparing this to the figures from 2020, the growth surges to an impressive 105.1%.

But a closer look reveals a somewhat different picture.

- For the past four years the monthly rate at which new subscribers are signing up has been falling, from 5.3% in 2020 to 3.7% last year.

- Trials, the most common form of getting people to sign up, are not converting to paid subscriptions: in 2020, the trial-to-paid conversion rate was about 60%; in 2023 it had fallen to 50%.

And I wonder how many of those people actually realised they were signing up, since in most cases companies require some form of payment mechanism to get those trials. The Paramount+ subreddit (a Recurly client) is littered with painful stories of folk who didn’t realise they hadn’t canceled their trial. One guy lost $250. In its white paper Recurly recommends a trial period of no more than 7 days before payment kicks in. Once again: if the product was so good, why do you feel the need to pressure the user into a financial armlock so early on?

I don’t have an easy answer to all this. Everyone seems to be in on it: try to cancel a New York Times subscription (call during US office hours, wherever you signed up). I’m still trying to find out why I’m still paying for a newsletter which moved from Substack to their own platform, without any apparent paper trail. While I managed to get one of the payments stopped by my neo-bank, I was told they couldn’t block any future transactions from the provider. (Paypal is much better at this, allowing you to cancel a recurring payment without any fuss and I’m going to shift everything across to that. I would advise the same.)

My bigger worry is this: as everything becomes subscription-based, two things are going to happen:

We’re going to lose access to things we care about

Subscriptions don’t leave you with anything, most of the time. The most civilised version is that practiced by the likes of Tinderbox, one of my favourite Mac apps, which requires an annual fee entitling you to updates during that year, which are yours to keep if you decide to stop (or pause). But most times subscriptions don’t leave you with anything. Those carefully curated playlists on Spotify? All those emails on Gmail? Gone, unless you’ve downloaded all your emails first, and unless you use illegal downloaders in the case of Spotify.

We’re going to find it harder to assign a value to things

I have used Setapp for several years, a subscription-based app store for Macs and iOS, with a wonderful array of apps. But at what point have I overpaid? I’m not sure. Depending on how you calculate it I’ve saved $1,920 or lost $898.

The good guys are going to have to find a better way

I love subscribing to people whose work I love. From an Australian creator of amazing dioramas to a mad British scientist in rural France, I offer meagre sustenance via Patreon. Until a recent cull I was a paid subscriber to more than a dozen Substack newsletters. And this is the thing: while these methods are a great way to support independent content, they don’t scale. When we as consumers add up how much we’re spending on subscriptions we realise it’s a lot more than we thought, and we have to take action. Sadly that means opting for a $10 monthly streaming service, while cutting two $5 per month Substack newsletters. It’s the little guy who loses, unfortunately. They’re doing great work, but so are a lot of others, none of whom can really scale beyond the one-man-and-a-dog model to compete with the behemoths.

So we’ll see changes. We have to. Substack writers will have to band together and form partnerships, offering discounts or freebies to subscribers. Bundling will become the norm, both for big players and small. The New York Times bought The Athletic and offers a financially attractive bundle. It wouldn’t surprise me if they folded dozens of Substack writers into a similar arrangement.

And that’s the thing. We may well find our way back into a more centralised model not unlike the one we thought we were disrupting. Newspapers consolidated pamphlets, advertisements and other printed matter because they could enjoy economies of scale; I see it inevitable that something similar happens.

Cable content networks bundled dozens of channels together to offer a take-it-or-leave-it proposition to consumers back in the 80s and 90s. As studios and platforms vie for your attention it seems inevitable they’ll further consolidate beyond the platform subscriptions that Amazon Prime, Netflix and Apple already offer.

This would all take us back to something we thought we’d got away from. I have enjoyed the transformation of entertainment that Netflix has ushered in. I even like Spotify’s ability to help me find songs from my childhood I really should have grown out of. But at what cost?

There is another way. I spend a lot more time digging around for video and audio that isn’t on these platforms, such as Bandcamp, where a lot of musicians allow you to pay what you want for their work. And Youtube, far from becoming a cesspit of clickbait and rabbit holes, can actually provide some extraordinarily erudite and enlightening content, often asking only for a donation on Patreon.

Subscriptions in themselves are not bad. They enabled a flourishing of music, theatre and art, for example, from the 19th century. Subscription allows creators, producers, providers to plan ahead, to be sure that the interest in their creation will last (at least) the year. It also allows a closer relationship between creator and subscriber. Substack and Patreon have helped revive this engagement.

The problem, then, is that the Subscription Model has bifurcated, between one where the subscriber feels closer, is closer, to the producer, and one where the opposite is true. On that model there is, instead, a faux closeness, driven entirely by AI and algorithms, but which is always trying to steer whatever excuse for a conversation takes place into upselling, or, if the subscriber cannot be deterred from cancelling, by offering a far cheaper price, a pause, or some other sop to keep them. In other words, the only time a subscriber may be offered something which is not available to them is when they threaten to leave.

In other words, the only time a subscriber may be offered something which is not available to them is when they threaten to leave.

The owner of an alcohol-free bar in Liverpool, SipSin, told BBC Radio Four this week that the bar had to close when it became apparent that drinkers of non-alcoholic beverages don’t tend to drink more than two and instead prefer to chat. Not the regular drink-more-need-more alcohol crowd. The interviewer asked her, Heather Garlick, what she planned to do next. She wasn’t sure, she said, but was thinking of a subscription/membership type model.

To me this captures the purpose of subscription models well. The idea is to create something that can endure, by ensuring that users and provider are committed to some sort of financial arrangement over the longer term. The publican is assured of income; the patrons are assured of somewhere they can go and find others of a like mind. (The book subscription market is doing something similar to the point where it’s worth $11.7 billion, with subscribers getting a curated box of books each month.)

Subscription is about demonstrating confidence that what you get in the future is going to be as good as what you’re getting now.

It is not a method of hoodwinking and impoverishing your customer. This should go without saying, but apparently needs to be said. In their response to a call for input to the UK government’s Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum Work plan last year, the UK charity Citizens Advice found that

consumers in vulnerable circumstances and from marginalised communities are at the sharp end of these practices and suffer particularly bad outcomes. We found that 26% of people have signed up to a subscription accidentally, but this rises to 46% of people with a mental disability or mental health problem, and 45% of people on Universal Credit.

Let’s not drag these practices any lower than they already are. Let’s instead try to reinstill some of the magic of paying for something you’re really excited about, confident that someone somewhere is using your money wisely and with the aim of keeping you hooked — without no dark patterns in sight.