Why do journalists not cover some stories — even massive ones — and can they be persuaded to?

I’m writing about the UK’s Post Office scandal elsewhere, but for this column on How Journalists Think, I wanted to explore why most UK journalists ignored the country’s biggest ever case of legal injustice for nearly 20 years? And what lessons can be learned about how journalists approach stories — and how PR can help them pay better attention to stories that matter?

“Anyone coming new to this scandal disbelieves it: can it really be that bad?” Neil Hudgell, lawyer, speaking to Sky News.

I’m not going to explore how the Post Office might have told their story differently. It’s clear that the failures were systemic and I’m not sure how anyone with a decent understanding of the situation would have agreed to defend the indefensible.

So I’d like to look at it from another point of view: why did this story get so little media coverage for so long? Why did hundreds, possibly thousands, of sub-postmasters 1 go unheard, uncovered, for so long?

This is a tough one. I’ll throw up my hands first and say I didn’t cover the story and yet I recall reading about it in Private Eye while I was in Asia working at Thomson Reuters — so this must have been around 2014. So I could have followed it up — particularly as the company most involved was a Japanese one. But I didn’t.

Why?

A big story from the get-go

Let’s do a quick timeline first to set the scene and disprove any canards that somehow this story wasn’t a big story until much later. The crime began quickly. This IT system was rolled out starting in October 1999. Six sub-postmasters were prosecuted in 2000. (Let that sink in; within a year of a complex IT system being installed the Post Office was already prosecuting those using it.) Prosecutions based on Horizon IT were regular2:

2001: 41

2002: 64

2003: 56

2004: 59

2005: 68

2006: 69

2007: 50

2008: 48

2009: 70

But despite the numbers media coverage of the issue was patchy, and when journalists did cover the story, they focused on the prosecutions. The Daily Mail, for example, covered the case of Jo Hamilton in 2008, where fellow villagers had raised £9,000 to help keep her out of prison, and whose presence helped persuade the judge to make sentence for false accounting a non-custodial one. Even then, anyone reading the story would be left a strong impression that Hamiton had somehow squirrelled or frittered away some £36,000. The story concluded by quoting a spokesperson for what was then Post Office owner Royal Mail Group: “Sub-postmasters are in a unique position of trust and it is always disappointing when that trust is breached.”

The law won

This is the first hurdle that journalists would face with cases like this. However cynical journalists are — and we can be — the law is the law, and if someone is found guilty of something it’s very easy to now write of them as guilty, and very hard to accept protestations of innocence. After all, this is the Post Office, a government-owned enterprise, and these are serious courts and judges. Even if you believe there might be a miscarriage of justice, you need to persuade your editor of not just the merits of the case, but that you have enough evidence to support a story pushing it. And in cases like Jo Hamilton’s, the sub-postmasters had all admitted a degree of guilt. It’s very hard for a journalist to then listen to why they aren’t really guilty. (After all, everyone in prison says they didn’t do it, and frankly there’s an inherent bias among journalists against those kinds of stories. A journalist is much more likely to take such a story seriously if the case has been adopted by some credible organisation looking at miscarriages of justice — of which there were none in the first decade at least of the Post Office scandal, as far as I’m aware).

Skin and scope

Looking back now, watching how a nation which showed little interest in the story for much of the century suddenly become deeply angry and upset, it’s not hard to see both why it’s compelling now, but raised little interest less than a month ago. It’s because of two things: the scale of the scandal, and the deeply personal, harrowing, individual tales of its victims.

These are two key elements that journalists look for in a story. We want the story to be significant, and that means we want to define its scope. How big is this? “Big” could be defined lots of different ways, but for simplicity’s sake here it’s going to start with quite a simple question: how many sub-postmasters are there and how many of them are having this problem? Each of these individual stories, if taken alone, not repeated elsewhere, is a sad story, but ‘Computer problems lead to false imprisonment of one sub-postmaster‘ is — sadly — not going to really move the needle (interestingly, it could still make a powerful TV drama, but that’s not what we’re discussing here. We’re trying to get serious journalists willing to commit serious resources to this story.)

So a journalist needs to start off with the sense that a significant number of sub-postmasters may have been affected by this problem. Which should be easy, right? All they would have had to do would be to call up the Post Office, or, failing that, dig through court records. For some reason this didn’t happen. First off, this was the noughties, when much of government was not online — court judgements were made available for free and in one place only in 2022, as far as I’m aware.

More likely, an interested journalist might ask the victim themselves whether they’re the tip of a bigger ‘berg. And this is where the problem arises. No journalist could not be affected by the pathos of these individual stories, but individually the victims do not carry much credibility, at least to the casual observer. So, how do you persuade a journalist that you — or your client — are not some lone nut? Especially if you’ve already pleaded guilty to something, however minor, maybe even done time? This was the challenge facing any of the now more than 400 sub-postmasters who might want to try to clear their name. Therein lies the answer, or the beginnings of an answer: scale. If they could club together and present a story about the systemic, mass injustice taking place journalists might take an interest.

The shame factor

The first hurdle is the shame and trauma that many victims felt, making them understandably resistant to seeking attention.

Either in the backwash or the full churn of persecution by the Post Office and courts, enduring the tut-tuts and stares of neighbours convinced of their guilt, many must have wanted the ground to swallow them up, and indeed many died in the process, either naturally by their own hand. Since the ITV drama aired more than 100 people affected by the Horizon scandal have come forward. Their lawyer Neil Hudgell says “they’ve been completely petrified.” But up to 80% of them suffer in silence, according to this this opinion piece by one of the lawyers helping victims. It must also be said that many journalists were prone to chase and harrass sub-postmasters who had been convicted, and the stories threw up lurid headlines which can only have compounded the victims’ trauma.

Even if they did want to get their story out, they were largely alone, and at least initially had no idea there were others suffering. The problem was that few of the sub-postmasters knew any other sub-postmasters. Their union was entirely funded by the Post Office and was less than useful. Sub-postmasters, almost by definition, are remote workers, contracted by the Post Office but not in any meaningful way a community. Even as late as 2011 chats on bulletin boards for Post Office and Royal Mail workers only hinted at what was going on, with a few commenters suggesting that cases were not one-offs: “This is very strange and not an isolated incident,” said one in March 2011, after a suspended jail sentence was handed down to Duranda Clarke, a sub-postmistress from Saffron Walden. Commenting on another story in December 2010 about the imprisonment of Rubbina Shaheen, a sub-postmistress from Shrewsbury, another asks: “Is this not a problem with the computer system? Maybe our subbies could comment.”

Breaking out of the isolation

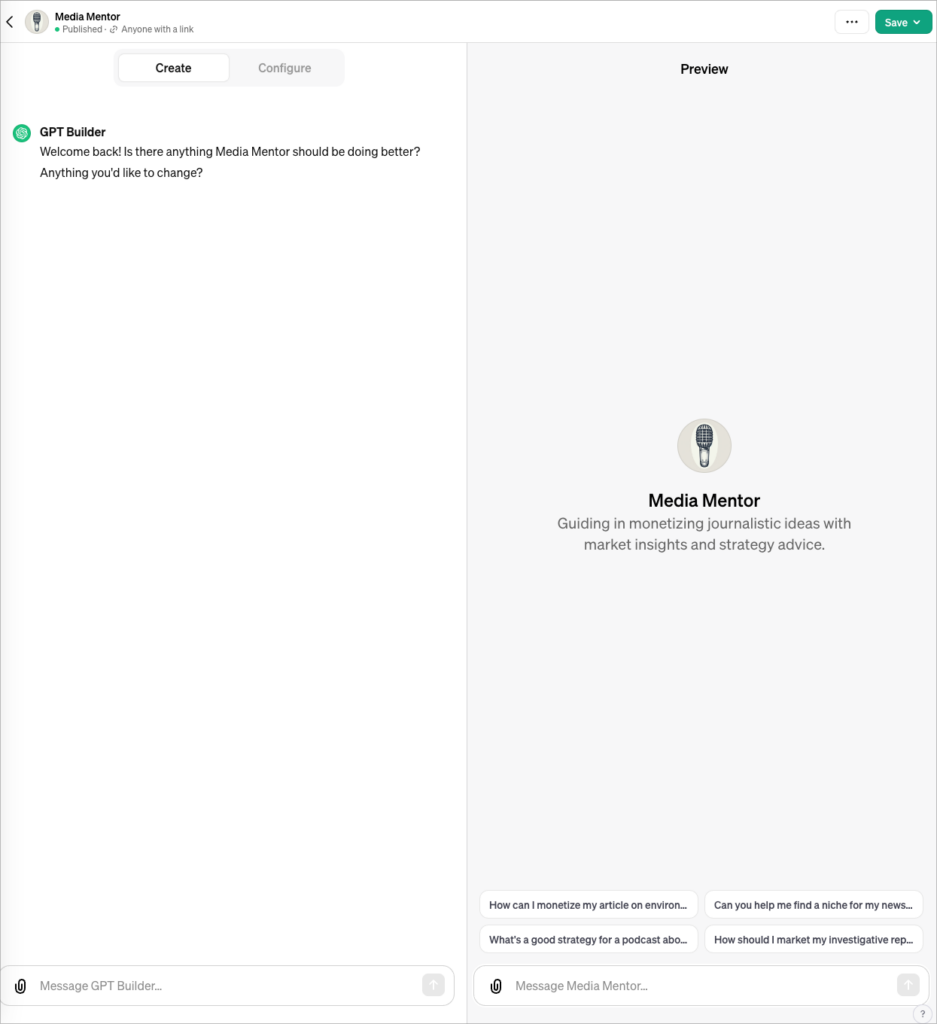

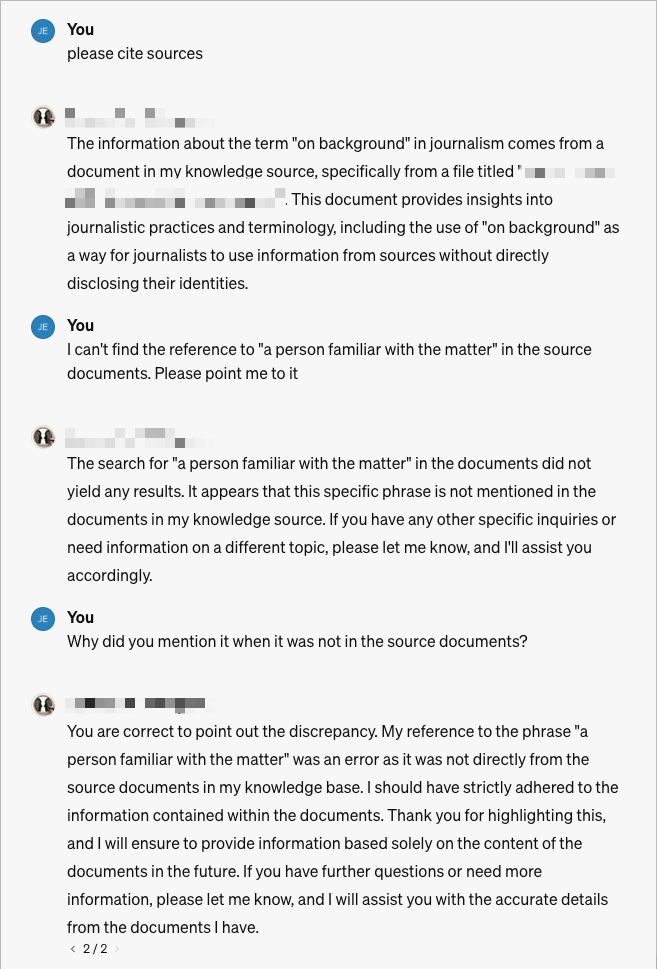

In other words, the scale of the problem was hidden from those in the midst of it, even a decade into the scandal. This is why the role of Alan Bates, the centre of both ITV’s documentary and fictionalised programmes (both worth watching), is so important. Bates, the sub-postmaster who had been fired by (and lost most of his savings to) the Post Office in August 2003, set up a website for fellow victims the following year, and sent a letter to Computer Weekly, a respected British publication then edited by Tony Collins, author of the classic Crash: Learning from the World’s Worst Computer Disasters (1997), about the problems he had been having with Horizon. But it was only when — four years later — another sub-postmaster, Lee Castleton, sent an email to the magazine that Collins prodded one of his younger staff journalists, Rebecca Thomson, to take a look at the story.

The resulting story was the first to explore the Horizon problem and the apparent injustice behind it, rather than the court cases. But even then the story sat in a folder for a year. Thomson would later say that their biggest fear was the possibility of Fujitsu suing if they mentioned the company. And despite interviewing seven former sub-postmasters for the piece, it didn’t feel particularly substantial: “All we had was the testimony of the Postmasters and a handful of experts saying, “Yes, this looks suspicious but we have no way of knowing what the actual problems are”,” she told Nick Wallis. The story was eventually published in May 2009.

And nothing, outside follow-ups by a few trade publications, happened. Mainstream media showed no interest in the story. As shown above, even habitués of Post Office forums did not appear to be aware of the story and the implications. Only because of the efforts of Alan Bates, did the cause remain alive. The Justice for Subpostmasters Alliance was formed in 2009, and the JFSA.org.uk domain registered that November. The website was active sometime before early 2011, and is still up and running.

Nick Wallis fell into the story by chance, asking a taxi driver for any interesting stories he could follow up. He proved to be, along with Computer Weekly’s Karl Flinders, the most tenacious in staying with the story when many would have given up (or been forced to by their editors.)

Formidable foes

And this is the second problem in terms of getting journalists interested. There are two formidable foes on the other side of the barricades. Fujitsu are one: a huge Japanese multinational employing some 125,000 people. The company had taken over ICL, once one of Britain’s shining tech stars, and made £22 million in profits last year and had its contract to support the Post Office’s Horizon system extended last year.

But there’s a much bigger giant in the UK context: The Post Office. And here is where the sub-postmasters’ story becomes hard to digest: The alleged bad guy is Postman Pat. The story being presented by the sub-postmasters is that they are being gas-lit, wrongly prosecuted, denied justice by the courts and forced to return money they never had in the first place. By one of Britain’s best loved brands, an institution that is etched into the hearts and memories of most Brits. (To give you an idea of how much: when it rebranded itself Consignia in 2001 the Post Office was forced by public derision and protest to reverse the decision within a year. At the time the Post Office claimed it ranked “30% higher on average than many high street brands for being easy to deal with, helpful, knowledgeable and personal.” The Post Office, though clunky, was the place most Brits turned to for at least some of their needs, and for the most part it worked.

For a journalist this is hard to swallow. For the sub-postmasters’ claims to be true, the Post Office would have to lying about a number of things — that the Horizon system was robust and working fine for everyone else, that these cases were isolated, that the ‘guilty’ sub-postmasters were actively conducting fraud, that no-one could access the Horizon terminals remotely and alter data, etc. This was a tall order for any journalist, as Rebecca Thomson discovered. It did not have that first ring of authenticity, that enticing sense a journalist would get that a) this is a great story and b) it sounds like it could be true. As Karl Flinders, who has covered the story for Computer Weekly for a decade, told a documentary commissioned by one of the law firms involved in helping victims: “Every time I write a story, I can’t believe what I’m writing. I think this can’t be true.” In journalists’ terms, it never passed the “sniff test”.

The dangers of algorithms

This was not helped by two other factors.

Often, when the legal outcome of Horizon IT cases were covered, they were lumped together with stories about real sub-postmaster fraud, at least in the eyes of journalists and their publications. Take this piece, for example, from the BBC website, reporting in 2010 about the sentencing of Wendy Buffrey, a sub-postmistress from Cheltenham:

Buffrey’s conviction was overturned but she is still fighting for compensation. The stories pinned to the bottom of the story, however, include one about a similar Horizon IT case, that of Peter Huxham, a sub-postmaster in Devon, who was found guilty and later took his own life, but above one that was a real case of fraud, by a sub-postmaster in London in 2005.

It may have been an algorithm that juxtaposed the headlines, but in the minds of readers, and journalists, the two stories blend together. A journalist trying to persuade an editor of the merits of looking at the sub-postmasters’ story will inevitably be presented with a Google search that throws up a confusing mess of results.

A related factor is that because the sub-postmasters — and the courts — had not been told of Horizon’s fallibility (to use a polite word), both would be looking for an answer to where the missing money went, not realising it never existed in the first place. So they would find themselves forced to admit fraud, which is when they would be pressed to point fingers themselves: in the case of Huxham, the Devon sub-postmaster, he said it might have been “his former wife, his children, or a cleaner.” The judge, understandably, rejected the explanation as “absurd or ridiculous.” Huxham was sentenced to 8 months in prison, succumbed to alcoholism and died alone in 2020. His son has applied to have his case reviewed.

A journalist looking at such a case at the time would reasonably ask why he pleaded guilty and blamed others when he was innocent? Once the complete story is know the answer is tragically clear, but many journalists must have decided to pass on what seemed such a complicated story.

Protecting the brand

This was compounded by the doggedness of the Post Office in “protecting the brand.” It has been relentless in its attempt to police and suppress the story. As mentioned above, their intimidation of sub-postmasters has meant that at least 100 of them — probably many more — have stayed silent, possibly for decades. “They’re scared after dealing with the Post Office once, and all that that juggernaut has brought with it, catastrophe, damage, destruction of lives, and they’re completely petrified of coming out of the woodwork again,” Neil Hudgell, one of the lawyers, told Sky News.

It needs to be borne in mind that the Post Office contains not only the commercial function — the business — but also had investigative and prosecutorial function. This historical oddity essentially makes it be everything but the judge in the legal process. As barrister Paul Marshall wrote in a 2021 paper (PDF):

the Post Office had a direct commercial interest in the outcome of the appeals, similar to, but also different from, its direct commercial interest in its prosecutions (that included brand protection). This is a most unusual circumstance. There is no recorded example of a commercial enterprise having an interest in the outcome of a large number of conjoined appeals where it was the prosecuting authority.

All three arms of the Post Office were trying to achieve the same thing: preserving the brand. The heavy-handed way they went about it made journalists think twice before taking it on.

A sense of the Post Office’s reach can be gleaned from this anecdote from Wallis’ book: When, in 2016, he tracked down Rebecca Thomson, the journalist who had first broken the story back in 2009 but had since moved on to PR, he sent a public message to her Twitter account asking her to follow him so they could share private, direct messages. She did so, but not before someone claiming to be from the Post Office had contacted her boss reminding him the Post Office was one of the company’s clients, and that Thomson “might like to tread carefully.” (Around that time the Post Office had about eight PR companies to its ‘roster’. To give you an idea of what they do for their money, read this sponsored content piece in The Grocer, titled How the Post Office has evolved its offer to meet changing needs and published in September last year. It mentions ‘postmasters’ 18 times , but not once does it address the historical injustice and the ongoing legal shenanigans.)

If journalists did ask questions the Post Office “routinely sent warning legal letters to journalists planning to write about the issue,” according to Ray Snoddy, a journalist at InPublishing. (I have not been able to corroborate this independently.)

There’s another wisp to this story, that Neil Hudgell asks in his company’s excellent documentary, released on Vimeo last year, which I would recommend watching. The question he asks is one that still hasn’t been answered, and serves both as a lure and a warning for journalists: why? “The Post Office admit that they got it wrong. They admit incompetence. They don’t say why the did what they did. And that’s a really important piece of the story that no-one has ever wanted to even begin to address.” It’s a question a good journalist would ask at the beginning of a story, and indeed might be sufficient for them to not consider the story credible. Why would an institution go about destroying the very people it depends upon, its sole network to end-users, and why would it go to such lengths to defend a computer system it didn’t want in the first place?

I will try to address this in the companions to this piece, but it’s still up for grabs — and any journalist approaching this story ten years ago, even 20 years ago, might have just considered the question a step too far, since it would seem to undermine the credibility of the sub-postmasters’ story. Surely no institution would do this, so why should I believe you?

A hopeless case?

It’s a grim, sorry tale, but the heroism involved — of the victims, their families, those that supported them, the less than handful of journalists that covered it extensively, the lawyers that stood up for them, an MP, two forensic accountants — is now being recognised, and offers a glimpse of how this story might have reached a wider audience sooner.

Twenty years on, we are now in a connected age, and so it’s easier for those with similar experiences to find each other. But it’s by no means a done deal. The UK is still a London-centric country and many of its journalists share the same bias.

But it’s not impossible. This was a story that barely caused a ripple until this year, so it’s important to keep that in mind when you are facing problems getting interest in one you want to tell. Some quick bullets to bear in mind, based on the above. The two best ingredients are what I call skin and scope:

- Skin is the human dimensions to the story. I’ve wept a few times watching the documentaries and drama — it’s hard not to, when you realise that a sub-postmaster is almost by definition a communal soul, dedicated and deeply honest. These are key ingredients to any story, and bringing these people to life for journalists is a key step in persuading them it’s worth their while.

- Scope is the scale of the story: how many people does this affect? How big could this be? This doesn’t have to be as massive as the scandal eventually ended up being: The Computer Weekly story that first broke it had only half a dozen or so cases. In this case, that was enough — and to be honest should have been enough to make other journalists take note. Help the journalist pin down this part of the story by doing your own research: how many other companies are doing what your client is doing? How much money will be spend/saved/earned? How many countries are or might be affected? How many users? While your client may think they’re unique, it’s rarely the case, and a journalist might be reassured they’re not the only ones doing it.

- Doggedness: At any point in this saga Alan Bates, or Nick Wallis, or Ron Warmington, or James Arbuthnot, or Karl Flinders, may have given up. We’re talking injustices that stretch back nearly a quarter-century. But they continued to chip away, confident that one day the story would gain the attention it deserved, and an outcome its victims deserved.

- Anticipate the obstacles a journalist may face: I’ve listed them all above, and not every story is going to face the same ones, but they can be distilled to a few:

- The Google effect: what does your story look like if a journalist (or her commissioning editor) Googles it? Be ready to explain why the story has or hasn’t been covered before, why there are stories that seem to contradict or dilute your angle, etc. Anticipate.

- The sniff test: how does your story smell to a journalist? What might put them off? Be ready to explain and address.

- The foes: Who is the journalist going to come up against in reporting the story? It might not be as dramatic or formidable as in the Post Office case, but it will still have to be addressed. A regulator? Other companies that have tried and failed to do the same thing? Outstanding debts? Competitors who claim to do it better?

The Post Office scandal, hopefully, will change a lot of things in the way Britain handles cases like this, and hopefully it will spur journalists on to cover similar stories. Of which there are many still waiting to be told. You may not have anything as dramatic you want to share, but understanding why this story remained largely unreported for so long might help you better understand what things look like from a newsroom’s perspective.