This is the first of a series of pieces based on Mary Meeker’s recent deck about AI.

It can be bewildering and discombobulating to try to absorb the rapid rise of AI, and I can understand why many of us choose to ignore it, dismiss it as horribly overhyped, or throw up our hands in despair. All of these reactions have some justification. But I think it’s worth taking a step back and trying to place what is happening in some context. Doing so might help in accommodating what is happening, even to draw some benefit and comfort from it. A 340-slide deck may not sound like a good way to do this, but I’ll try to condense it. I hope it will be worth it.

The deck is from Mary Meeker, a veteran of Silicon Valley and someone who, over the years, has got a lot of things right. She’s also at an age, not unlike myself, to have witnessed the miracle of Internet-based technologies and so can see a bit more clearly than those who grew up with the Internet (essentially anyone younger than 45). A slide from a Mary Meeker deck, therefore, is usually worth 100 slides from most other folk, so her recent dump on AI is worth the time. (With some caveats I’ll leave to a later post)

One of the peculiarities about AI is that while it threatens the livelihood of millions, it’s also one of, if not the fastest adopted technology/ies in history. It took 33 years for the internet to reach 90% of users outside North America; it has taken ChatGPT three. It took Netflix more than 10 years to reach 100 million users; it took ChatGPT less than 3 months.

But this is not where the real change will come from. Let’s face it, ChatGPT is easy to adopt because it’s quasi-human. We interact with it in the same way we communicate with our friends. We haven’t adopted generative AI as a technology so much as allowed its anthropomorphic version to insert itself into our lives. This is unsurprising: we have known since the 1970s that we humans tend to accommodate anything, live or dead, into our lives if it hits certain (but not all) anthropomorphic notes. A cute animal (behaviour, features), a favourite teddy-bear (inertia that we take to be stoicism and loyalty), Alexa (voice, responsiveness). A sign our adoption is complete is that we then yell at it when it doesn’t do what we want.

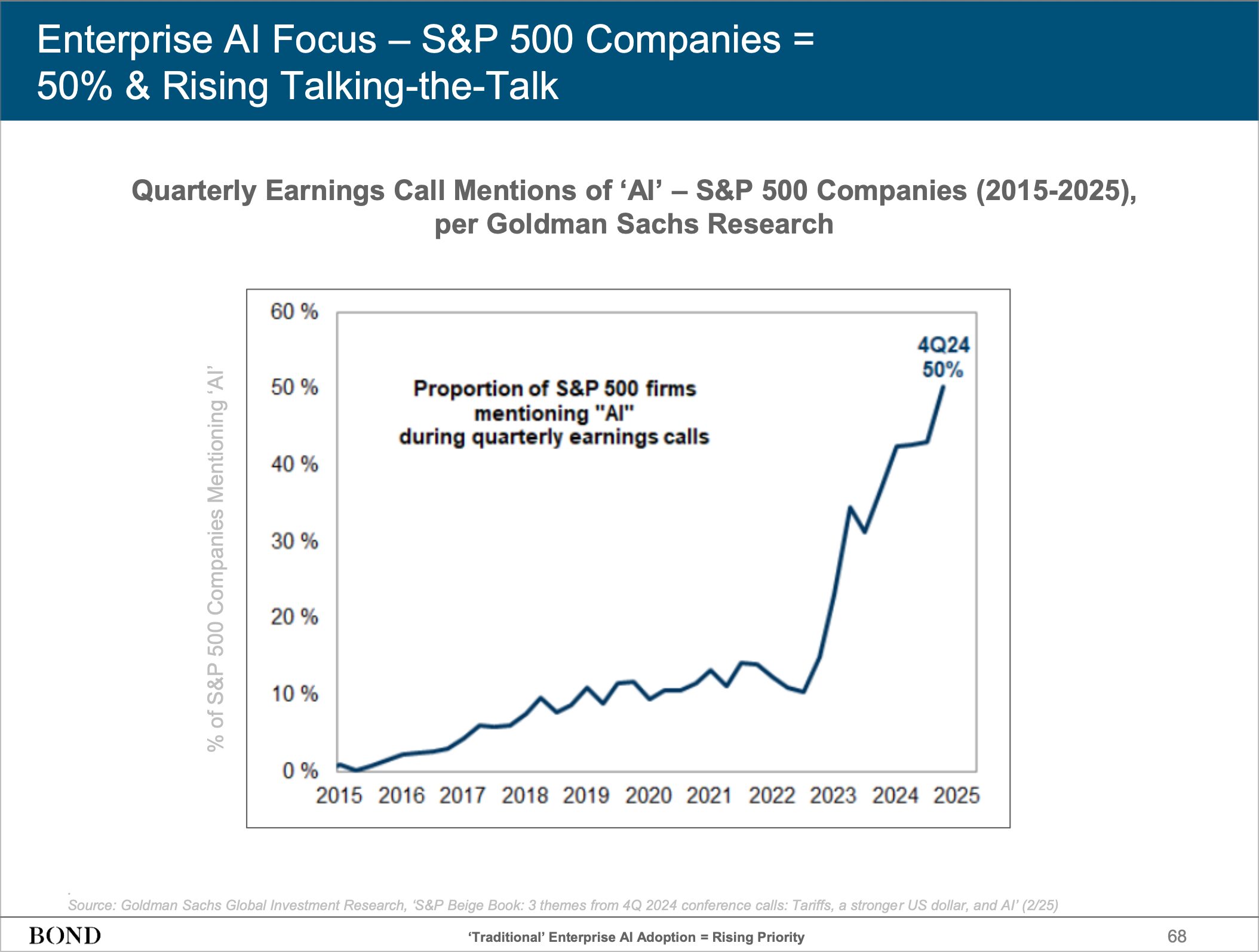

So our embrace of the technology is not really where change is coming from. The change is in how fast company CEOs are adopting AI — and want to be seen to be adopting AI. In late 2023 the proportion of S&P 500 firms mentioning AI during quarterly earnings calls was about 10%, a number that had risen slowly from zero since 2015. By 2025 that proportion had risen to 50%. (Slide 68)

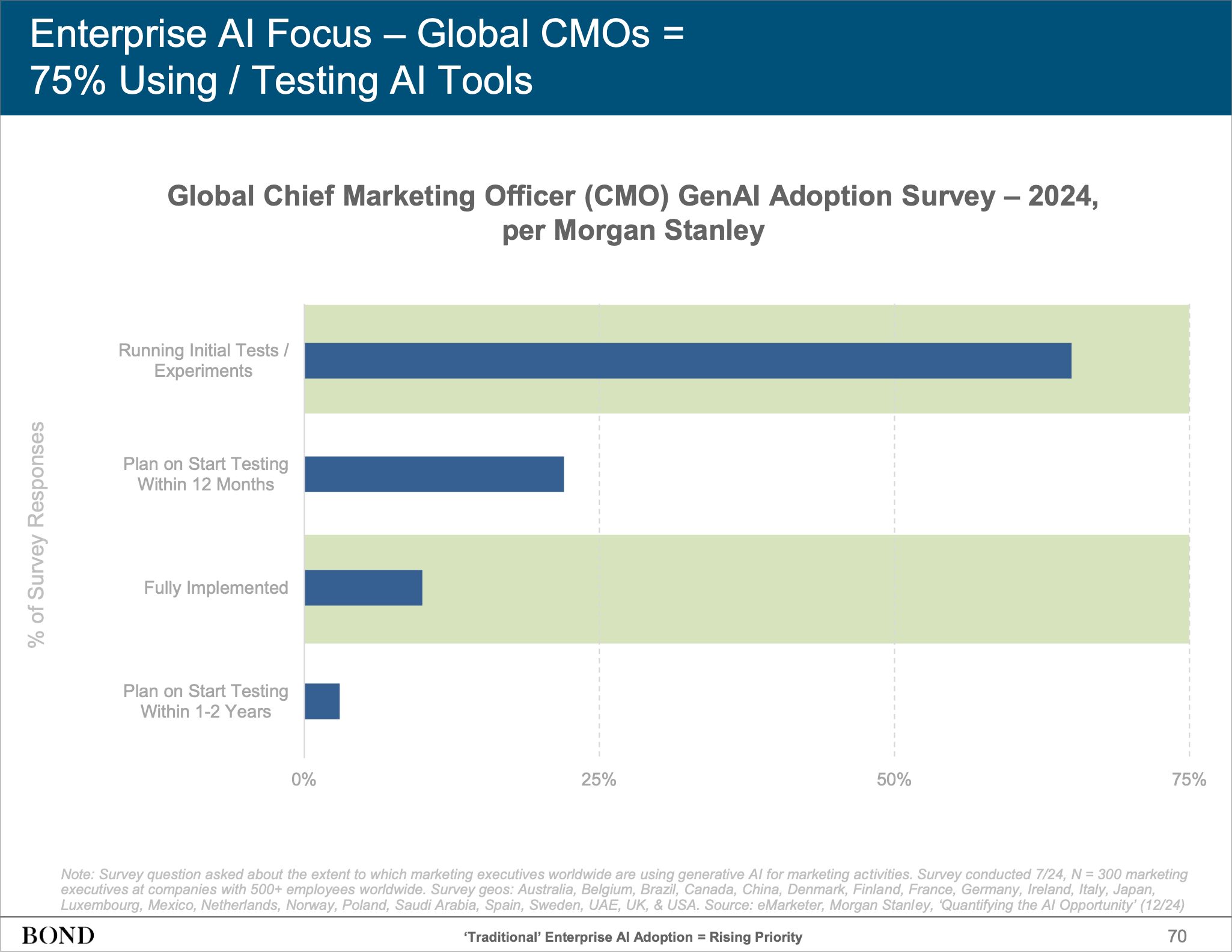

And this is not just CEOs barking whatever buzzwords their media and IR teams are throwing them. In a survey of CMOs by Morgan Stanley in December 2024 two thirds said their companies were running initial tests and/or exploring using Generative AI for marketing activities. (Slide 70)

Agent AI

So where are those tests taking them? The chatbot image of generative AI is not what is really getting CEOs excited. What is getting them excited is the next wave of AI: agents. Agents form a “new class of AI… less assistant, more service provider”, in Meeker’s words. Where chatbots operate “in a reactive, limited frame”, agents

are intelligent long-running processes that can reason, act, and complete multi-step tasks on a user’s behalf. They don’t just answer questions –they execute: booking meetings, submitting reports, logging into tools, or orchestrating workflows across platforms, often using natural language as their command layer.

Meeker compares this shift to that of the early 2000s, which

saw static websites give way to dynamic web applications –where tools like Gmail and Google Maps transformed the internet from a collection of pages into a set of utilities – AI agents are turning conversational interfaces into functional infrastructure.

The key thing to understand here is that an agent is not “responding” so much as “accomplishing”. They don’t need much guidance — indeed, they may quickly need no guidance, but instead autonomously execute, in Meeker’s words, reshaping “how users interact with digital systems “from customer support and onboarding to research, scheduling, and internal operations.” This is where the bulk of the enterprise appetite is going, not just experimenting but “investing in frameworks and building ecosystems around autonomous execution. What was once a messaging interface is becoming an action layer.” (All quotes are from Slide 89)

Strip away the glitter here and it’s this: An agent is essentially a human in disguise (or multiple humans.) Once briefed, it works independently, executing, learning, improving and extending. And companies are investing in the infrastructure to support this autonomous activity. You don’t have to be paranoid to see how agents, barely acknowledged a year ago, are now the focus of significant investment, which would likely have been directed towards investment in human-led processes.

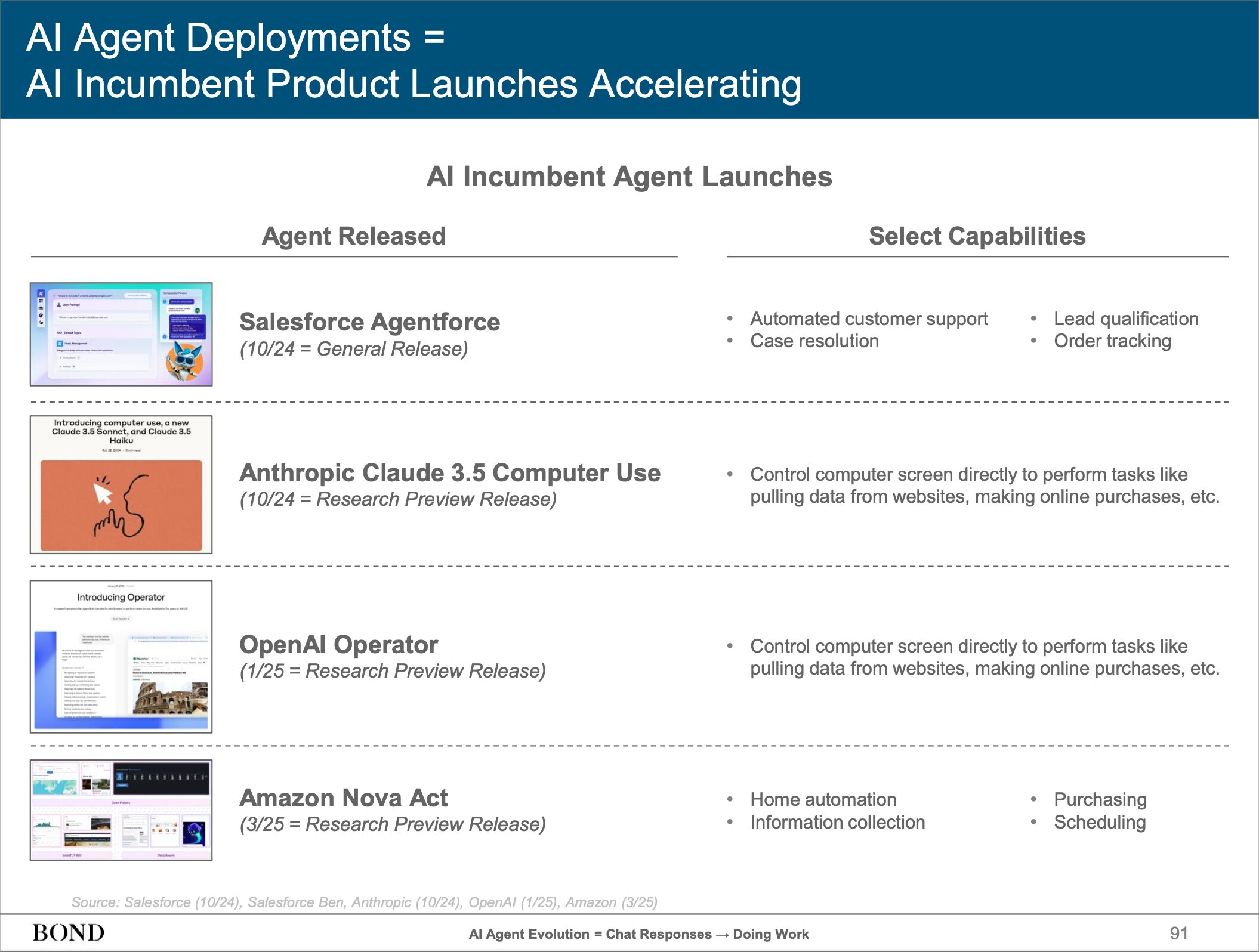

Meeker cites a handful of examples: Salesforce’s Agentforce not only handles customer support but resolves cases, qualifies leads and tracks orders. Anthropic and OpenAI have agents that can control a user’s computer screen directly to handle tasks like pulling data and making online purchases. (Slide 91). Where AI was a research feature, it has since 2023 become a CapEx line item. It has become, in the words of Microsoft President Brad Smith, a “general-purpose technology” like electricity — “the next stage of industrialisation.”

Mary Meeker again:

The world’s biggest tech companies are spending tens of billions annually – not just to gather data, but to learn from it, reason with it and monetise it in real time. It’s still about data – but now, the advantage goes to those who can train on it fastest, personalise it deepest, and deploy it widest. (Slide 95)

This is where size helps. Training a model costs more than $100 million. Anthropic’s CEO has said that these costs could rise to $10 billion — per model. Inferences, while falling in unit cost, will likely “represent the overwhelming majority of future AI cost,” in the words of Amazon CEO Andy Jassy, because training is a periodic cost — done from time to time per model — while inference costs will be constant — every query. In Meeker’s words:

The economics of AI are evolving quickly – but for now, they remain driven by heavy capital intensity, large-scale infrastructure, and a race to serve exponentially expanding usage.

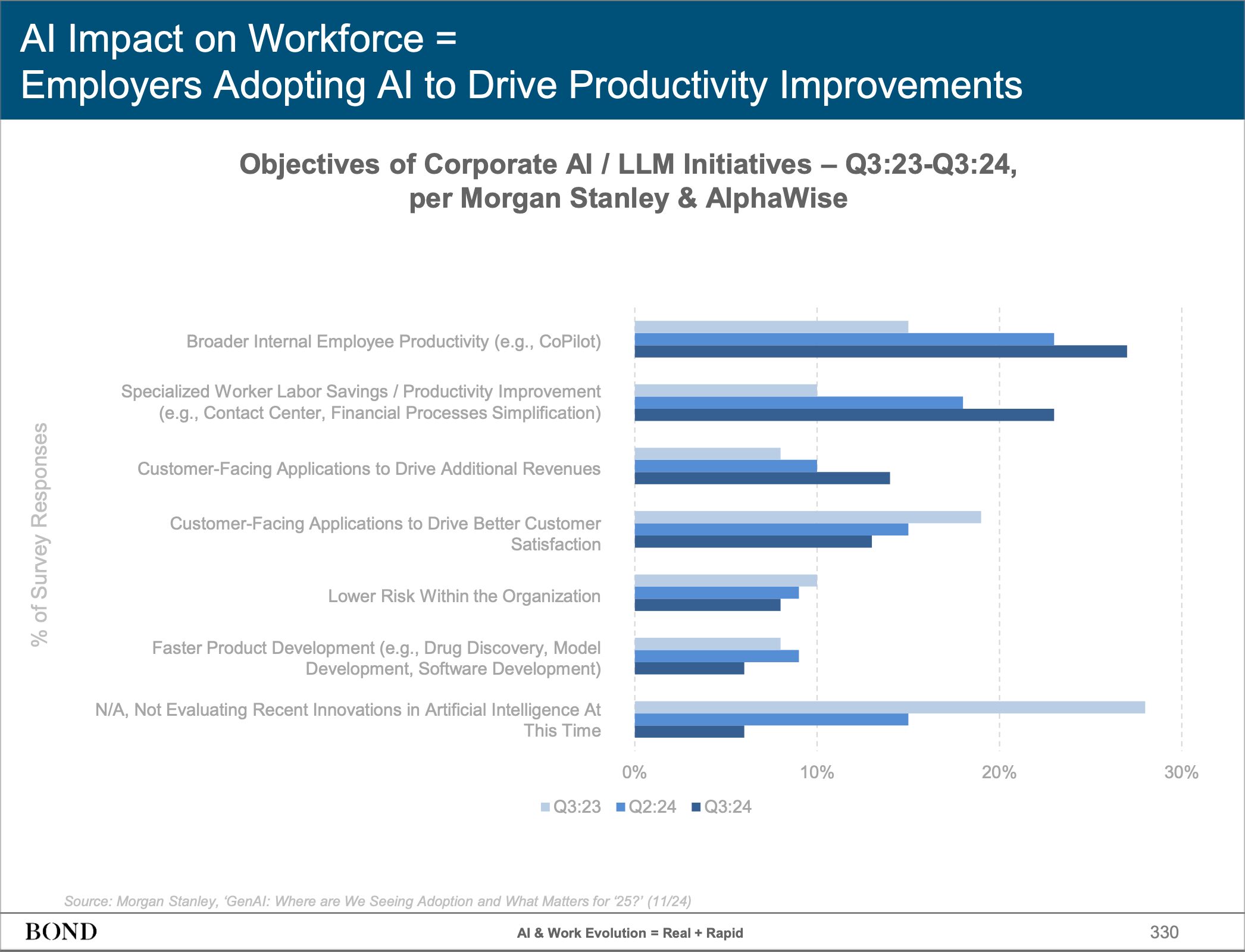

Meeker doesn’t walk us all the way down the path, and I’ll go into more detail in the third of this series of pieces — but it’s clear that worker productivity is top of most corporate agendas for embracing AI. She quotes a Morgan Stanley survey from November 2024 (Slide 330) where workers are top of mind: the largest adoption of AI was focused on employee productivity, the second highest worker savings.

Meeker avoids reaching her own conclusions on this. Instead she gives over a whole slide (Slide 336) to NVIDIA’s Jensen Huang, who paints a picture in the rosiest of terms. Yes, he says, jobs will be lost. But only to those who don’t take the opportunity. In fact, he argues, there’s a shortage of labour and anyone who takes advantage of AI will benefit. Here are the two bookends to the slide’s overall quote which probably encapsulate his thinking best, and illustrate the fist inside the velvet glove:

It is unquestionable, you’re not going to lose a job – your job — to an AI, but you’re going to lose your job to somebody who uses AI… I would recommend 100% of everybody you know take advantage of AI and don’t be that person who ignores this technology.

Meeker offers no annotation to this slide on the subject of workers. In the next couple of pieces I’ll try my hind