This is the second in a series of pieces trying to explain what happened in the UK’s ongoing Post Office scandal and why it matters. The first was about the lack of media coverage the story received for the first 20 years. (It can be found on How Journalists Think, on the Loose Wire Blog and on my LinkedIn feed. )

This one was intended to look purely at the technological side of things, but first need to understand the human element in all this — how a project like this happened in the first place, and why so many serving and former employees of the Post Office failed to come forward and address the scandal at any point in the 20 years it was churning sub-postmasters out of the legal meat-grinder.

By way of reminder, some brief background:

A flawed computer system in the UK led to the conviction of at least 700 individuals who ran small Post Offices, and while nearly 100 of those have been overturned, at least 60 sub-postmasters have died without seeing justice or compensation, at least four by their own hand. All were prosecuted on the basis that a computer system set up by Fujitsu, Horizon, worked perfectly and so could not have been responsible for the errors that led to sub-postmasters being accused of creaming off funds in their Post Office account.

The Post Office, currently being dragged through an enquiry, prefers to call the scandal the “Horizon IT Scandal”, presumably because it doesn’t include the words “Post Office.” It euphemistically refers to the fact the system was riddled with bugs and at least one backdoor as being “primarily concerned the reliability of the Horizon computer system used in post offices and issues related to Postmasters’ contracts and the culture of Post Office at the time. It’s a bit like the owners of the Titanic telling a post-sinking enquiry that the episode “primarily concerned the reliability of the ship.”

What it doesn’t say is that Post Office staff supposed to help subpostmasters navigate the system would say the system was not to blame, no one else was having any problems with it, and insisting the subpostmasters cover any discrepancies. And then charging them with theft.

It’s a grim tale that has been burning slowly in the background for 20 years, with only a handful of dedicated journalists (and sub-postmasters) pushing for justice. And it’s probably too early to draw some lessons, but one thing is clear: It was not in the interests of the company, the Post Office (owned by the government, but with its own board, effectively separating itself from its owner), and Fujitsu, the company providing the system (the contract is worth £2.3 billion, and is still ongoing), to admit that the system was flawed. But beyond that there’s more.

Pre-history of a scandal

It probably comes as no surprise that the project was doomed from the start. This is not to say that hundreds of innocent people would be convicted, but the project itself was deeply flawed, even before it was built.

Here’s a brief account of what happened. I’m indebted to Eleanor Shaikh, whose dogged research and excellent analysis is one of those small demonstrations of heroics that should be properly acknowledged and rewarded. (You can find the fruits of her research at the: Justice for Postmasters Alliance resources page.)

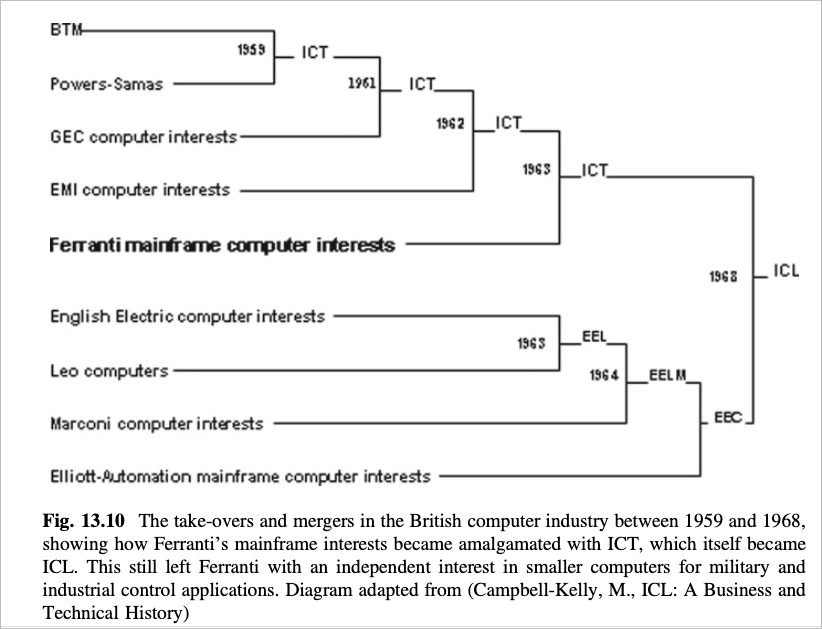

The company that became Fujitsu UK was something called ICL, itself a Frankenstein’s monster cobbled together by government in the 1960s desperate to keep Britain’s once-great computer industry alive, a British flagship to compete with IBM. ICL survived mostly through government contracts; the government took a 25% stake in the company in the 1970s and, at least for that decade, ICL flourished.

In 1968, with government encouragement, ICT was merged with all the UK’s remaining mainframe computer manufacturing companies to form ICL.

By the early 80s it was in trouble, but Margaret Thatcher overcame her free-market instincts to give it loan guarantees to maintain a British computer industry. Around this time it abandoned some of its in-house development to buy Fujitsu chips. In 1990 Fujitsu cemented its hold on the company by buying a 80% stake in 1990. ICL was now, to all intents and purposes, Fujitsu UK.

Around the same time the Post Office was beset by fraud — losing nearly £100 million between 1991 and 1992 to fraudulent social security (welfare benefit) payments. The government, which owned (and still owns) the Post Office devises something called Project Horizon in 1993, which it hoped would handle the £56 billion more securely through a swipe-card system atop an automated process . A contract worth £1 billion was put up for tender in 1994. IBM competed but ICL-Pathway (the name of Fujitsu at that time) won, signing the deal in 1996.

The Goal Postmen

In less than a year Fujitsu was burning through £10 million a month, but had nothing to show for it — not even in a controlled environment could to demonstrate a “satisfactory, sustained environment”. The Post Office and the Benefits Agency kept moving the goalposts — 323 formal requests to change the original contractual requirements over three years — and it was clear that Fujitsu did not have the capability to do it. At the same time the project was becoming more ambitious, wrapping in other functions a sub-postmaster currently did by hand. By January 1998 the government was considering ditching the whole thing.

A few months later the Benefits Agency served Fujitsu with a formal notice of breach of contract. Fujitsu refused to accept the notice and then threatened to stop working on the project altogether unless it got a better deal. The Benefits Agency delivered a coup de grâce when it announced it was ditching swipe-card payments for direct payments to bank accounts. As Shaikh puts it: “In one swoop, Fujitsu’s potential income from the project had been reduced to zero. On top of that, the Post Office was looking at losing a third of its customer base overnight.”

This put the government in a difficult position. During 1998 Fujitsu had bought the remaining shares in ICL so there was no ignoring it was a Japanese company. The future of Horizon was kicked up to Prime Minister, Tony Blair, to make a decision. ICL — Fujitsu UK — was by now not only completely in bed with the government, but it was hogging the sheets: It won a £200 million contract with the Department of Trade and Industry for something called “Project Edgar”, and signed another called “Project Libra” with the Lord Chancellor’s Department; the following year it signed a £680 million contract with Customs and Excise.

The Domino Effect

But Horizon was still the big fish, and if it got away it was widely accepted in Whitehall, according to Shaikh, “that ending the contract in its entirety would spell the downfall of ICL”. The Japanese government was not unaware of this fact. The real head of Fujitsu UK, Michio Naruto, collared the UK ambassador to Japan and left him with a clear picture: “any threat to ICL’s continued viability would have profound implications for jobs in the UK and for bilateral ties,” the ambassador warned. (Naruto would later earn a CBE for his troubles, a rare gong for a Japanese national.) Blair’s government, desperate not to upset the Japanese and to prevent a domino effect of collapsing ICL-related projects, scrambled around for a solution. The Treasury, in particular, was keen to keep the Post Office on an even keel — a rare profit-making enterprise in the government’s portfolio, it had contributed some £2.4 billion to government coffers since 1981.

But the Post Office was not enjoying the ride. Even as ministers were scrambling around it couldn’t make the system work, and blamed Fujitsu, which it blamed for a lack of support, design and documentation. In early 1999 it concluded :”We have been unable to gain a high level of assurance in the adequacy or suitability of the service.” The Benefits Agency were out, and the Post Office wanted out too. At some point this month senior members of Fujitsu marched in to see Blair, and while we don’t yet know what happened there, they had put the PM on notice: make a decision by May. Blair, terrified of the optics should they scrap Horizon, upset the Japanese, derail any number of other Fujitsu projects and write off hundreds of millions, possibly billions, of pounds, ordered the project go ahead.

Appalling people

By October, ready or not, “full automation” had begun as Horizon computers were rolled out. As Eleanor Shaikh put it:

This is how, at the behest of the Prime Minister, Horizon’s untested core of dubious provenance came to be the IT backbone of the nation’s iconic Post Office. It was a politically expedient deal which cemented ICL/Fujitsu as the trusted supplier of IT in the foundations of New Labour’s Modernising Government agenda.

The Post Office leadership quickly pivoted. While the board remained unimpressed by Horizon, there were salaries to be earned and the big ticket project gathered a momentum all its own, with little regard for the sub-postmasters themselves. Frank Field, then a minister for welfare reform, warned parliament in 2000 that something was seriously off. He reported that the board had little appetite for serving the post offices and those who ran them. Karl Flinders (another hero of Post Office coverage) wrote that Fields said: “I did not merely talk to colleagues and read the papers, I visited the project partners. Had it been my responsibility to do so, I would have sacked the members of the Post Office board, who were appalling people. They were short-sighted and partisan.”

The people problem

Indeed, the story of Horizon from the point at which it was clear it was not going to go away is largely a story of human failure on an epic scale. We know how badly the sub-postmasters suffered, and we have taken aim at some prominent villains in the piece, but the egregious behaviour of nearly everyone involved in the Post Office begs some serious questions.

“What awful people.”

How, for 20 years, could an institution remain indifferent and unquestioning about the litany of failure — to properly install a system, to properly train and support those using it, to question whether so many postmasters were on the fiddle (and if so, whether the recruitment that sourced these people was flawed), to raise any questions within about the appropriateness of this conveyor belt of cruelty? I am happy to be corrected, but I could find no whistle-blower from within the Post Office during this period, despite its own promotion of World Whistleblowing Day. (Richard Roll, who spoke out in 2015, was an employee of Fujitsu. The only case I can find is one at Royal Mail, which was split from the Post Office in 2012, and even then that person was dismissed after raising concerns, leading to a court case in which Royal Mail was ordered to pay her £2.3 million in compensation.)

We need to look at the institution itself, which employs under 4,000 people. What were they doing in these 20 years? And the Fujitsu teams working on the project? What were they doing? The moral bankruptcy did not just exist at the top. They were the ones who led, but everyone else followed. Where were the whistleblowers from within the Post Office themselves? I know it is distasteful, but I can only compare it with the most studied (and still poorly understood) case of moral blindness in recent history: Germans both during and after World War II.

Mind your language

Firstly, there is the phenomenon of identifying one group as “the other”, making it both easier and more bureaucratically acceptable to prejudge them and justify what amounts to persecution. Dehumanizing always starts with language, argues Brené Brown, citing David Livingston Smith (Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others) and Michelle Maiese (Autonomy, enactivism, and mental disorder: a philosophical account) , and this can be easily seen in the way the Post Office treats, both formally and informally, the sub-postmasters. In one email written by then Post Office investigator Gary Thomas they’re described as “all crooks”, when he explains why he’s pleased to get his hands on some particular emails:

“Because I want to prove that there is FFFFiiinnn no ‘Case for the Justice of Thieving Subpostmasters’ and that we were the best Investigators they ever had and they were all crooks!!”

(Once again, thanks to Nick Wallis for the great detective work, and journalism, where much of this stuff comes from. )

This notion of sub-postmasters as of a particular type, an ‘other type’ of person, can be found in the official document: where one required investigators to categorize (PDF) suspects ethnically — including terms such as ‘Negroid types’, “Chinese/Japanese types” and “Dark Skinned European Types” (and don’t get me started on why Siamese, a term that went out when Siam became Thailand in 1939):

This might be put down to excessive bureaucracy, perhaps, but there was clearly racism and contempt among those managing the Horizon system and working with sub-postmasters. Amandeep Singh, who worked for a year on the Horizon help-line, staffed by Fujitsu employees, described the situation thus:

Postmasters right from week one would be upset, crying frustrated as they struggled to reach equilibrium on the transactions. The floor on these days was most toxic with vocal characters in Squad A, unchallenged by managers who looked away as all Asians were called Patels, regardless of surname. Shouts across the floor could be heard, saying “I have another Patel scamming again”. They mistrusted every Asian Postmaster. They mocked Scottish and Welsh Postmasters and pretended they could not understand them. They created a picture of Postmasters that suggested they were incompetent or fraudsters. \

“I know nothing”

Then there’s the “this wasn’t something I was involved in so I know nothing” defence.

Some have presented themselves to the enquiry — intentionally or unintentionally — as witless. They didn’t know what was going on, anything they signed was written by someone else, they felt slightly bad about what was happening, but not enough to do anything about it. Jarnail Singh, once head of criminal law for the Post Office, who was even reluctant to acknowledge that he fulfilled that role. “I know if I had to go to court and actually physically see these people, then I wouldn’t be able to do the job. I think I would have left a long time ago. At the end of the day, this was a paper exercise,” he told the inquiry. This is not a million miles from what historian Hannah Arendt called Schreibtischtäter or desk murderer, where bureaucrats stay insulated from what they’re enabling, ordering or approving.

A stone’s throw from this is the tendency for those in position of authority to claim wrongdoing wasn’t something they were aware of. Michael Keegan, who was Fujitsu UK CEO from May 2014 to June 2015, leaving the organisation in 2018, successfully appealed to the Independent Press Standards Organisation, IPSO, in 2022 over news coverage that he said inaccurately linked him to the Post Office scandal, arguing that he did not have “line management responsibility” for the Post Office account in this period, and that he had only learnt of the sub-postmaster’s litigation from press coverage in 2019. (Keegan previously worked for the Royal Mail Group/Post Office, and had joined Fujitsu UK in 2006.)

While I am not suggesting he was responsible for the Horizon project, it does require a leap of faith, given its size and value, that he was unaware of the massive wave of prosecutions underway, especially as he previously worked for the Post Office. Ignorance, real or imagined, of what is going on beneath someone in a senior position of course is nothing new. Adolf Eichmann claimed he was ‘a mere instrument’ in the Holocaust, saying he “was not a responsible leader, and as such do not feel myself guilty.” Eichmann was in fact one of the main organisers of the Holocaust. (Just to be clear, I’m not likening Keegan’s role in the Post Office to that of Eichmann in the Holocaust, just that claiming you did not have ‘line-management responsibility’ and therefore were not responsible is nothing new.)

Self-victimisation

Then there is ‘acquired’ victimhood. We now know who the victims are of the scandal, although there may be thousands more who have not come forward, or may have passed away. But that has not stopped some people from claiming victimhood for themselves. Take, for example, the above-mentioned Gary Thomas (I am again indebted to those who did the hard yards on this story, this time to Nick Wallis. He and others covered this story for years when no one was interested.) Thomas had once been a counter clerk before rising, if that’s the right word, to the Security Team (the ones responsible for the heavy treatment of sub-postmasters) in 2000. After the quashing of 39 sub-postmasters’ convictions in 2021, he wrote to the then chief executive of the Post Office, that he, too, was a victim, because he had now found out that all the evidence he gave “was incorrect and lies.” He concludes:

Can I ask the question and enquire why we have all been completely cast aside and left with not so much as a letter of communication or an apology whatsoever ?

Whilst compensation is being correctly awarded now to these Sub-Postmasters, I feel the employees instructed to conduct these prosecutions, arrests and searches have been completely overlooked.

The claiming of victimhood by those who might be more accurately described as those on the delivering rather than receiving end is well-documented in the academic literature. Harald Jähner, in his book Aftermath: Life in the Fallout of the Third Reich 1945–1955 describes the feeling of many post-war Germans:

The fate of victimhood that people volubly assigned to one another – known in sociology as ‘self-victimisation’ – stripped most Germans of any obligation they might otherwise have felt to engage with the Nazi crimes committed in their name.

Elsewhere, Michael Zank writes on Daniel Jonah [Goldhagen’s ] book Hitler’s Willing Executioners (https://www.bu.edu/mzank/Michael_Zank/gold.html) that

The prevailing attitude in Germany after the war was self pity, an attitude which left little if any room for attention to the greater suffering of others.

Conclusion

I was pondering the merits of such distasteful comparisons but sometimes a spade has to be called a spade. The abrogation of responsibility, and the apparent lack of empathy on display from a procession of officials and officers before the inquiry makes me think that, while ultimately it’s our worship of the computer that made this scandal possible (which I promise to address next time), confining it to that lets a lot of people off the hook. Those at the top made a series of very poor decisions based on political expediency, and greed, while those in the middle or lower reaches of the companies involved would seem to have either looked away, claimed ignorance, bad memory or deep ineptitude, in order to exonerate themselves.

Those corridors, too, need to be explored, investigated and cleaned.

And we need to draw lessons from how these projects are born, and how those who should be asking tough questions — and refusing to implement clearly wrong-headed and vindictive processes — can be encouraged to do so, and held responsible if they don’t. This isn’t going to end if a few gongs and bonuses are clawed back.

Thanks for reading, and, as usual, your comments and tips are very welcome.